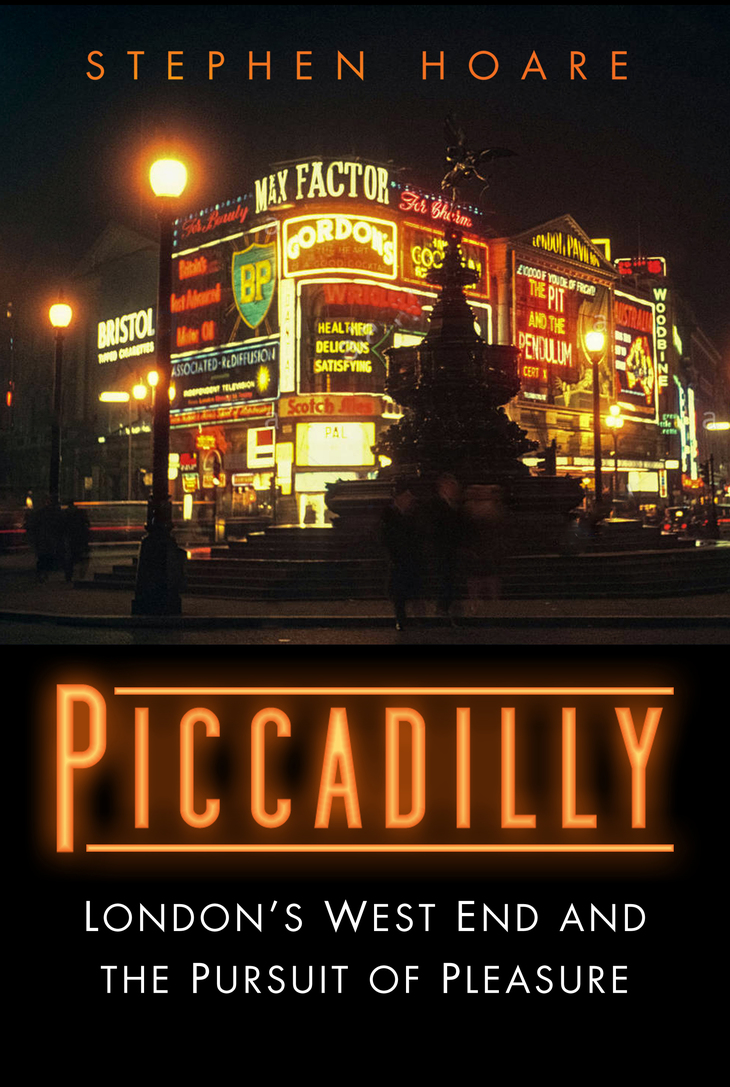

In this extract from Stephen Hoare's book, Piccadilly: London's West End and the Pursuit of Pleasure, we learn the illuminating history of the Piccadilly Circus adverts.

By the early 1900s there were already large advertising billboards on many of the buildings on Piccadilly Circus.

In 1904, the first electric sign spelled out ‘Mellin’s Food’ in 6ft-high letters above Mellin’s Pharmacy at 43 Regent Street. Mellin’s Food was a popular infant food supplement: a ‘soluble, dry extract of wheat, malted barley and bicarbonate of soda’. The advert read: ‘Mellin’s Food for Infants and Invalids: The only perfect substitute for Mother’s Milk’.

The year 1908 saw the installation of the first electric illuminated advertising billboards on the frontage of the Monico tea rooms. Illuminated advertisements for Perrier water and Bovril were quick to follow. A popular brand of beef tea, Bovril became the first product to be advertised by neon light in 1910. At a time when most domestic houses were lit by gas, electric and neon illuminations were a novelty that added to the area’s brash appeal.

The electric billboard was the latest manifestation of London’s confident and assertive advertising industry. Since the early 19th century, commercial enterprise and advances in printing resulted in unregulated billboards springing up on every vacant plot of land. Every empty wall was plastered with ephemeral printed notices and signage advertising shops, music-hall attractions, funfairs, property auctions and patent medicines. And with the development of industrial enamelling processes, railway stations and grocery shops were covered in colourful and virtually indestructible signage advertising everything from cigarettes to tea and soap powder.

Nevertheless, the London County Council disapproved of this buccaneering example of private enterprise. It used lamp and signage by-laws within the London Building Act of 1894 in order to prevent ‘the exhibition of flash lights so as to be visible from any street and cause a danger to traffic therein’.

The vaguely worded by-law was impossible to enforce. A scheme to redevelop the north and east of Piccadilly Circus and to rid the Circus of a ‘disorderly rabble of buildings’ also ran into the sand owing to numerous objections. Besides, the owners of buildings fronting onto the Circus — the Monico and the London Pavilion — regarded advertising signage as a valuable income.

With its fast-growing passenger numbers, the Underground also regarded selling advertising space at its stations and access tunnels as a major source of revenue. Advertising on the Tube not only had the advantage of being highly visible but also offered an opportunity for the railway companies to reinforce the message that the Underground offered opportunities for leisure. Day trips to places like London Zoo or the Thames at Chiswick were now possible.

The small horse-drawn buses were covered in enamel adverts for Hudson’s Soap, Nestlé’s Milk and Oakey’s Knife Polish. In the never-ending battle for consumers’ attention, Piccadilly Circus’s illuminations would very soon be put to the service of Gordon’s Gin, Guinness, Black and White Whisky and Sandeman’s Port.

London's West End and the Pursuit of Pleasure by Stephen Hoare, published by The History Press, is published on 1 September 2021, RRP £16.05