As even the most fleeting of tourists will find, London owes a huge debt to Sir Christopher Wren. Arguably the most famous architect in English history, you may well have visited his grandest projects, which include St Paul's Cathedral, the Royal Naval College and the south front of Hampton Court Palace. Yet one of his other designs in the capital lies significantly less noticed.

Tucked away in a leafy housing suburb of Sydenham, the spire of St Antholin's Church pokes through the rooftops. A curious local landmark, it stands independent from an actual building of any kind, so unassuming that no hint of its history is even mentioned through any plaques or signage.

Nonetheless, it is in fact a bona fide Wren design, one remnant of the 51 churches that the architect was charged with rebuilding after the Great Fire of London in 1666. While the remaining churches otherwise sit neatly in a cluster deep in the city — making St Antholin's steeple look somewhat of a castaway alongside the bell tower of All Hallows in Twickenham — the spire was similarly born within throwing distance of the Thames, and only saved by one determined city businessman.

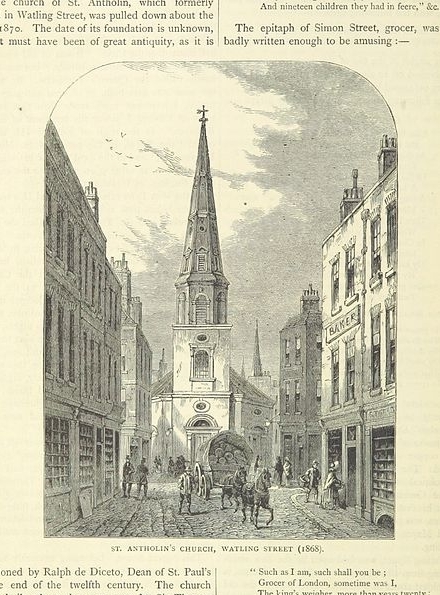

Records of the original church of St Antholin's stretch back to 1119. Originally named after Saint Anthony the Great, it was situated on Budge Row, formerly part of the huge Roman trading route Watling Street, which ran across southern England and still remains in parts of the city today.

Over the centuries St Antholin's underwent a number of rebuilds and extensions, with the last coming just a few decades before the Great Fire, according to The Churches of London, an 1839 chronicle by George Godwin and John Briton. Unfortunately, like everything inside the capital's ancient defensive walls, all the good work was soon undone by flames.

As with much of Wren's church work in the aftermath of the fire, it is not clear whether the steeple was actually drawn by Wren's own hand; his surrounding team did much of the legwork in his name. Nonetheless, unlike the comparatively plain main building, the steeple was an eye-catching design, leading Godwin to praise its "great powers of invention" and 16th century historian Richard Newcourt to note the "very curious spire" was all cut from freestone.

However, as the City of London rapidly expanded beyond its tiny peripheries, even the Wren name couldn't save his churches from threat of closure and by the early 19th century, St Antholin's was pegged for demolition.

Before the historic church was completely torn down, though, news of its demise reached the ears of Robert Harrild, founder of the pioneering printing company Harrild & Sons. As the story goes, the businessman had built up an affection for the building, looking upon it as he travelled to work, and so took it upon himself to at least save part of this mainstay for his morning commute.

At this point, Harrild had lived in Sydenham for years, and was a key member in establishing it as a functioning outer London community, even acting as a parish guardian. Clearly, he was rich enough to afford to buy the spire of St Antholin's for a sum of £5, but perhaps a greater testament to his social standing was his ability to actually convince contractors to both dismantle the spire piece by piece and relocate it to his garden in Round Hill in 1829.

Though Harrild's garden is now long gone, the spire remains — now incongruously surrounded by 1960s housing.

The spire became one of the early footnotes in Sydenham's understated cultural heritage. Quarter of a century later, the famous Crystal Palace (alas, another eventual fire casualty) would come to the Sydenham park now named after it. Not long after that, another local Christian monument rose to fame when the impressionist Camille Pissarro captured St Bartholomew's Church in his 1871 painting The Avenue, Sydenham.

And what of the rest of St Antholin's? The building was eventually demolished in 1875, with some of the proceeds of its sale funding a new church of the same name in Nunhead (which stood in its first form until the second world war, when, this time by bombs, it was again destroyed — poor old St Anthony).

In an age where all too often we see London's architectural treasures turned to rubble in favour of trendy offices or new-build apartments, the church's story is a somewhat sobering reminder that this is far from a 21st century problem.

As the spire of St Antholin's also shows though, businessmen needn't always be the villains – indeed, how our buildings could now do with a cheerleader as pesky, wealthy and respected as Harrild to fight their corner.