From Canary Wharf's ultra-modern glass to the Moscow Metro-inspired subterranean splendour of Gants Hill, London boasts some of the world's most aesthetically-pleasing stations. But out of the 270 tube stations on TfL's network, which ones are the fairest of them all? It's a tough call. So tough, in fact, that Pound Place — a blog from online lender Pounds to Pocket — ended up picking 82 favourites to turn into illustrations. By reducing them to simple, monochromatic sketches, the architectural quirks you might fail notice on a busy commute take centre stage.

For Pound Place, Piccadilly comes out on top as the most attractive Underground line, with 33 stationson the route making the list. Several of Charles Holden's iconic modernist stations — built in the 1930s as the line was extended further eastwards and westwards — have been singled out. Conversely, the Underground's newest line seemingly makes for far less picturesque travelling, with just three Jubilee Line stations making the top 82.

Have a gander at all of the illustrations, alongside some interesting tidbits from the original article's author. Did your favourite station make the cut?

Piccadilly line

Ironically, the most recognisable of the blue line’s stations is closed. Aldwych Station appears as an active, up-and-running tube station in a number of films, and as an abandoned subway in the Tomb Raider 3 video game.

Architect Charles Holden modestly described his stations as “brick boxes with concrete lids” – but architectural critic Jonathan Glancey claims Arnos Grove is “a total and entire work of art.” Glancey listed Arnos Grove alongside the Empire State Building and Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao as one of the world’s twelve greatest modern buildings.

When Boston Manor station was rebuilt in the 1930s, the architects kept the original 1883 platform and other features, so stepping through its modernist façade is a journey through time before you even set foot on a train.

Bounds Green’s heritage listing identifies the station as “a distinctive variant on the ‘Holden Box’ Piccadilly line station design, with a unique octagonal ticket hall, which responds appropriately to its suburban setting while boldly announcing its presence through its Modernist style.”

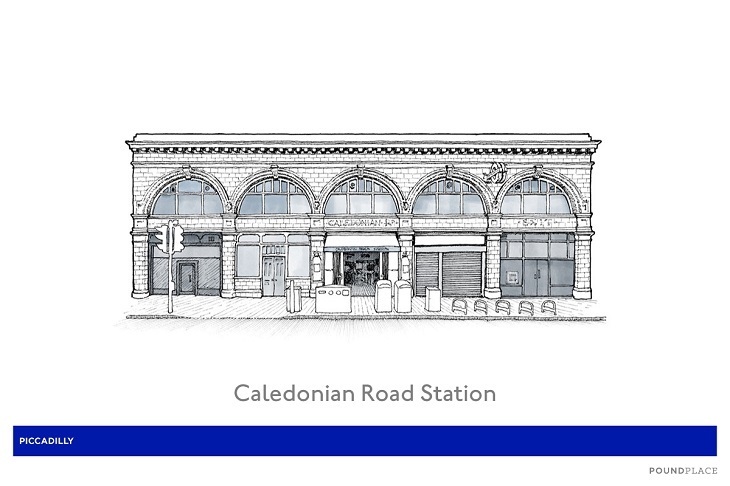

The ticket office at Caledonian Road station was updated in the ‘80s, but straight and spiral staircases to the platforms retain many original features such as a pomegranate frieze, bronze handrails and — at the bottom — metal roundels from 1910 bearing the station name.

Cockfosters station is more sympathetically preserved than a lot of Holden’s other stations. And its ship-shaped ticket hall and wide, single-storied structure — flanked by two towers — make it (almost*) unique. (*see also: Uxbridge)

Built on the site of Victorian actor William Terriss’s favourite bakery, Covent Garden is clad in the familiar ‘Oxblood’-red glazed tiles that adorn many a classic tube station; in this case, however, the bloody tint is a cruel reminder of the murder of Terris by rival actor Richard Archer Prince — particularly since Terriss is said to haunt the station.

Holloway Road was home to the world’s first functioning spiral escalator — but it never ran. Inventor Jesse Reno built the 10-metre high, 30 metre-per-minute helix before the underground even had conventional escalators installed; but it went unused (probably due to safety concerns) and remained hidden until 1988.

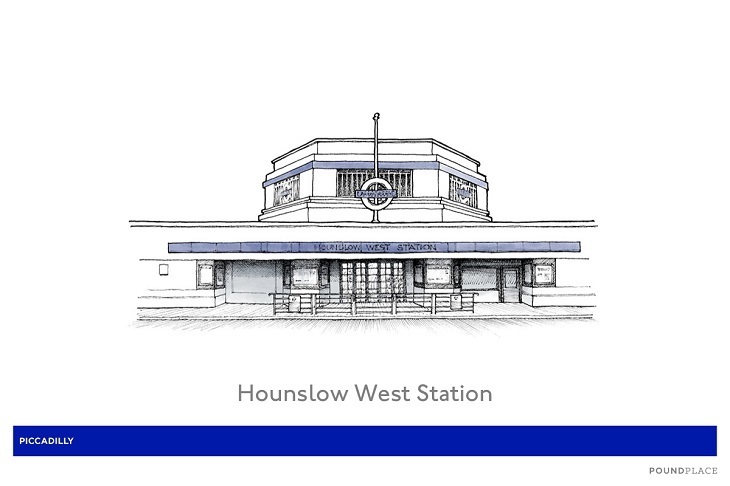

The ticket hall is Hounslow West’s key point of interest, being a ‘heptagonal double-height drum’ lit by a bronze chandelier formed of seven heptagonal lights — a veritable throne-room for the geometrically-inclined.

Opening in 1903, this station avoided the ‘Holdenization’ of other stations on the South Harrow branch in the 1930s — so its brick and concrete structure feels altogether less metropolitan and a little more rural.

You can still see the remains of the long elevated walkway from Weymouth Avenue to Northfields station — a temporary solution after shocked tube managers noticed that the station had been built very close to neighbouring South Ealing station and proposed the closure of the latter.

Oakwood is formed of a “double-cube” structure – a variation on Holden’s brick box principles after he delegated the design of this station to Charles Holloway James, an architect best known for his work on the garden cities of Letchworth and Welwyn.

Osterley is most notable (and noticeable) for the illuminated obelisk that stands proudly atop the station’s tall brick tower.

‘L’ shaped Park Royal Station is formed of a drum-shaped ticket hall, tower, and curving retail block. The ticket hall’s ribbon of clerestory windows give it the look of a film reel waiting to unspool.

The exterior of this station is pure poetry; according to its heritage listing, the “upper storey has timber Diocletian windows in keyed semi-circular arches with egg-and-dart decoration and cartouches between the springers of the paired bays, and modillion cornice.”

Southgate debuted as one of Holden’s most futuristic designs in 1933; its flying saucer roof is propped up, on the inside, by a central column in turn supported by a circular array of beams, interspersed with lighting fixtures that wouldn’t look out of place on the Starship Enterprise.

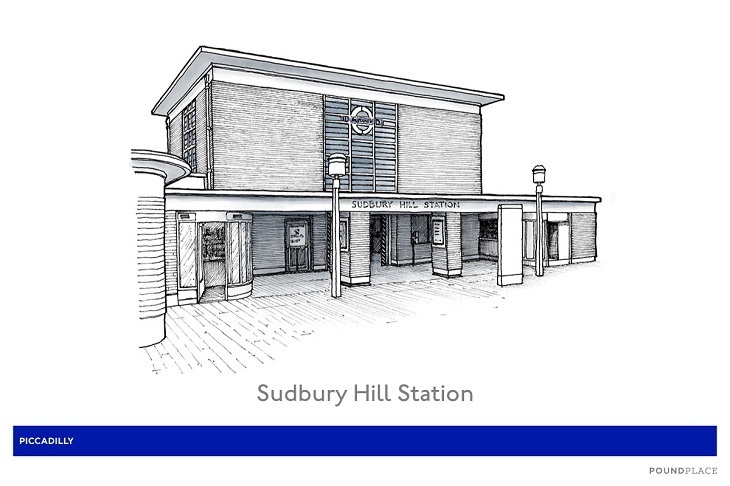

The red brick and Lego-like geometry of Sudbury Hill — complete with pillar box-shaped signpost outside — give the station a picture-book ‘British’ look. Fittingly, it is the tube station that is most popular with pigeons.

The twin towers of Turnpike Lane are in fact ventilation shafts that reach deep below the surface; from above, sunlight filtering through the high, segmented windows creates an ethereal atmosphere in the late afternoon.

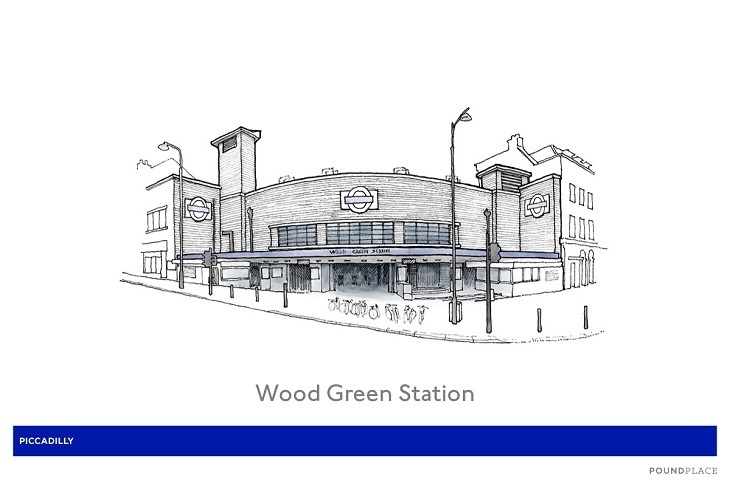

Wood Green enjoys protected status as “one of the best of Holden’s ground-breaking Modernist designs for the Piccadilly line extensions of the early 1930s.” The ventilation grilles were designed by Harold Stabler, who also designed the first official seal for the London Passenger Transport Board and a cap badge for the service.

Northern line

In 1940, the exterior of Balham Underground station survived a 1400kg armour-piercing bomb that crashed through the road to the tunnels below — the explosion itself was not deadly, but more than sixty people sheltering in the station died in the resulting panic.

Listed as one of London’s “five best tube station designs” by the Guardian’s architecture critic, Belsize Park’s expansive façade is tiled in Leslie Green’s distinctive oxblood red, and sits on a hidden 8,000-person air-raid shelter.

Designed by Stanley Arthur Heaps — Leslie Green’s assistant, who took over the job on Green’s death — is in the Neo-Georgian style and boasts a tiled pyramid roof, which clashes exotically against Heaps’ signature Doric columns.

Chalk Farm is something of a reverse TARDIS; on the outside, it’s has the longest frontage of all Leslie Green’s designs, yet the ticket hall is a very small and neat triangle which serves the platforms below via a space-saving spiral staircase.

Clapham Common boasts the most exotic architecture of the three Clapham tube stations, its domed cupola rising from a traffic island off the A3 dual carriageway. As one internet commentator notes, the building has “a faint whiff of Catholic chintz about it.”

Clapham South is a somewhat residential affair. Not only is it nestled underneath the Westbury Court housing block, but the tunnels were once used to accommodate Caribbean migrants arriving on the Windrush and visitors to the Festival of Britain who wanted a cheap place to stay.

There’s no better way to appreciate Charles Holden’s work on the stone temple of Colliers Wood station than while sipping a beer in the pub opposite — which is named after the architect.

The particularly British take on art deco that is East Finchley station is crowned by Eric Aumonier’s statue of an archer above the entrance. It points out the direction of what was once the longest tunnel in the world down below.

Hendon debuted in 1923 as a single-storey building more or less surrounded by fields in an area designated for suburban growth; by 1929, the station had become the central portico of a much larger building, and the focus point of the growing town.

The first station to have an electric lift, Kennington is crowned by a tremendous dome that originally housed the gears of the hydraulic lift that preceded it.

Mornington Crescent is another red-faced station, in this case notable for the particularly tall arches over the entrance; the upper parts of these have been “treated as glazed tympana and flanked by lugged architraved sashes,” which if you know anything about architecture you’ll know is pretty good.

A curved, white Portland stone façade gives Wimbledon Central a forbidding look as you approach; inside, natural light from the clerestories (high windows for extra illumination) makes it a more welcoming place to buy your ticket.

Tooting Bec is formed of two buildings, the secondary structure being a satellite entrance across the street. The old clocks on the platform were made by the Self Winding Clock Company of New York City.

Tooting Broadway is a standout feature of Tooting’s vibrant high street. One figure who doesn’t hustle or bustle, however, is the statue of Edward VII out in front.

Central line

The red brick Edwardian-era simplicity of Barkingside has the slight look of a pagoda, and was most likely designed by architect WN Ashbee — who was also responsible for the gigantic Liverpool Street Station, at the other end of the scale.

From the outside, Loughton’s vertical reach, post-art deco arched windows, and geometric design give it the look of a cinema; from inside, the barrel-vault roof combines with those same arched windows to give it the feel of a church.

The author didn't include a caption for Perivale station, but it's no surprise the northwest London building was included, given its Grade II-listed status. Designed in 1938, its construction was delayed by the second world war, and Perivale Station officially opened in 1947.

A somewhat forbidding and industrial presence on Eastern Avenue, Redbridge was to have been softened by a permanently-lit glass tower — but the project was downscaled due to post-war shortages.

Australian architect Brian Lewis designed a number of tube stations, but many of his ideas were modified by other architects after the second world war delayed construction. West Acton is the only station that matches Lewis’s original designs.

Gants Hill is the most eastern entirely-subterranean tube station of them all; perhaps appropriately, Holden’s design was inspired by the Moscow Metro.

Metropolitan Line

Chesham is something of a lonely station, the furthest from its closest neighbour in the whole network. It’s so remote (relative to the rest of London) that it the locals themselves had to fund the building of the station.

Charles W. Clark designed 25 stations in all — his urban ideas were more classical, while features such as Watford’s hipped dormers and chimneys lent a more homely feel to suburban destinations.

District Line

Chiswick Park station may not scream ‘mainland Europe’ at beholders, but its rotunda was probably inspired by Krumme Lanke Station in Berlin and Urbain Cassan’s Brest Station in France. Architect Charles Holden toured northern Europe a couple of years before Chiswick was erected, and the region seems to have left its mark.

Earl’s Court is a fancy looking building for a fancy area. It was the first station to get an escalator, in 1911 — and is also the site of the last remaining blue police telephone box (or TARDIS to you and me.)

Upgraded as early as 1905 to serve patrons of Chelsea’s newly built football stadium, Fulham Broadway’s historic station was closed a century later and transformed into a market hall — access to trains is now via a nearby shopping centre.

Even the footbridge at Kew Gardens station is Grade II listed; narrow with tall walls, this 1912 structure was designed to protect users’ clothing from steam train vapour.

Now 150 years old, West Brompton is a fabulous example of a well-preserved original Underground station – with features such as its cast iron footbridges still on view.

Bakerloo line

Technically the first station on the network, Harrow & Wealdstone was first built in 1837, although it was completely rebuilt in 1912.

Looking somewhat like a child’s drawing of a fire station (not that there’s anything wrong with that), Kilburn Park’s single-storied entrance is wrapped in shocking red faience (glazed ceramics). Faienced lettering above the bays complete the sense that this is a jolly nice tube station.

Maida Vale echoes Kilburn Park’s shiny red styling, known as the ‘Leslie Green’ style, inspired by the architect who designed many of London’s first stations. Green was commissioned, in 1903, to build 50 stations — but the stress of the project led him to an early grave aged just 33.

Jubilee line

The iconic blue coned wall of Southwark station may look a bit sci-fi, but it was actually inspired by an 1816 stage design for a production of The Magic Flute.

Clad in cream terracotta tiling, Willesden Green has the look of something you might spy in the window of an upmarket patisserie. You’ll know it’s time for tea thanks to a diamond-shaped cantilevered clock protruding over Walm Lane.

Stations on multiple lines

Each of the 11 stations on the Jubilee line extension was designed by a different architect, and Canary Wharf drew Foster + Partners. The designers of the Gherkin envisioned a site that’s strikingly modern next to the others we’ve seen, in its use of light, glass, and even a landscaped park overhead. Note: Canary Wharf is, of course, on the Jubilee and DLR — not, as suggested in the illustration, on the District and Central lines.

Westminster is a special story inside and out; on the surface, it is part of Portcullis House, an extension of the Houses of Parliament. But deep down, the criss-crossing of exposed walkways and engineering elements gives it the feel of a Piranesi etching, or the interior of Paris CDG airport. Note: That Central line label should actually be a Circle line one. Oops.

One of several stations to be rebuilt after parliament approved the Piccadilly line extension in 1930, Acton Town is another Charles Holden building, an almost-square box with that familiar concrete slab on top.

With its fancy canopy, original platform benches, and poster boards complete with 1920s enamelled signage, a visit to Barons Court is a step back through time.

One of just two stations with a heptagonal ticket hall, Ealing Common’s six-sided tower features glazed screens on each side to illuminate the space below.

The original Aldgate East was demolished in 1938, its replacement landing 500ft along the road where the train track was less curvy. Trains ran on tracks suspended from the ceiling while the new, lower platforms were dug out.

After being rebuilt between 1959-1961, Barking station was described by architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner as “commensurately modern in outlook and unquestionably one of the best English stations of this date.”

School-like in appearance, this Edwardian building boasts a long, yellow stock brick façade with red brick dressings.

It is Baker Street’s interior that is most noteworthy: yes, the famous Sherlock Holmes tiles that were added in the 1980s, but more particularly the light wells that deliver strange forms of illumination to the platforms from the world outside.

Farringdon station is an important hub between the past — such as the ghost of Anne Naylor and the striking neoclassical façade — and the future, when it will (eventually) become the main interchange between the new Crossrail and Thameslink services.

‘GPS’ is a peculiarity among tube stations, being formed of a massive, elliptical filled doughnut on a traffic island on a busy junction.

Moorgate is something of a ghost station, featuring unused platforms devoted to long-cancelled services and which bear the aesthetics of now-forgotten brand identities. (Trains still run on other platforms across the station).

As part of the overground network and an international hub, King’s Cross underwent major redevelopment in the first years of the 21st century, including the addition of more than 300m of underground passageways.

Yes, the station is impressive — but did you know that 23-24 Leinster Gardens, along the street, is a fake house? It’s just a façade — the original was demolished to allow steam from passing tube trains to pass up to the heavens.

55 Broadway is the entrance both to St. James’s Park station and the headquarters of Transport for London; it is a suitably monumental building, adorned by sculptures from noted artists such as Henry Moore and Jacob Epstein.

Blackfriars is beautiful in more than one way: its glass façade and steel structure, but also the fact that half its energy is supplied by the world’s biggest solar-powered bridge — Blackfriars railway bridge.

Entrance to the Bank station ticket hall is via the historic Bank of England complex; for added glamour, the platforms down below are curved so as to circumvent the bank’s vaults!

A Charles Holden box-and-lid design, Eastcote still maintains many of its original doors, platform clocks, and signs today.

Named after the farmer who owned the only building in the area when the original station was built, Rayner’s Lane is at the heart of a conservation area dotted with other fine examples of modernist and art deco buildings.

Built as early as 1904, Ruislip features one of only four remaining Edwardian all-timber signal cabins on the network.

Called on to fix an unsatisfactory design, Charles Holden simply reversed his design for Cockfosters (which happens to be at the opposite end of the Piccadilly line) and made it a little bit bigger so that it could also accommodate the larger trains of the Metropolitan line.

Beauty is more than skin-deep at Gloucester Road: one disused platform has been transformed into an art gallery.

Opening on Christmas Eve, 1868, South Kensington was substantially altered by Leslie Green and George Sherrin in 1907; the latter designed a street-level arcade, of which two original glazed shop fronts still exist today.

Artist John Maine created new façades and paving for the station during a pre-London Olympics refurb – using 150 million-year-old Portland stone.

Named after Robert Sidney, 2nd Earl of Leicester, who held a 17th century residence here, the station is now clad with neon signs and film stock iconography to reflect the local cinema scene.

You have to plunge below ground level to appreciate the beauty of NHG: while the entrance is a modest (if historic) set of steps, the ‘cut-and-cover’ structure (a trench dug into the ground and covered by a curved glass roof) gives the feel of a grand international station on the inside.

There are two buildings of note at Oxford Circus: Harry Bell Measures’ structure on Argyll Street and Oxford Street, and, over the road, Leslie Green's oxblood entrance (pictured) to the Bakerloo Line — now squashed beneath a tower of modern offices.

TCR is a monument to modern art. Pop artist Eduardo Paolozzi installed a thousand square metres of mosaic on the walls in the 1980s, while 80,000 tiles were used to install French artist Daniel Buren’s redecoration of the Oxford Street entrance in 2015.

The tube station at Waterloo is part of the biggest railway station in the UK. Just to add to its regal appearance, the surface level is lifted several metres above the ground to allow for the marshland underneath.

While there was an ‘upstairs’ booking hall when Piccadilly Circus was built in 1906, it became completely subterranean following a 1920s revamp. Today, artwork down below celebrates the life of Frank Pick, the publicity officer and later CEO responsible for the world-famous Underground ‘roundel’ logo and much of the tube’s art deco architecture.