This is a sponsored article on behalf of the Museum of London Docklands.

Inspired by Museum of London Docklands' Secret Rivers exhibition, we take a look at the little-known plans to reshape London's most famous waterway.

Can the Thames be moved? If the river is not to our liking, can we divert it down a different course?

Rivers are not as fixed as we might imagine. During the last ice age, when Britain was still attached to the European mainland, the ancestral Thames followed a very different course, eventually meeting up with the Rhine.

In more recent centuries, the river's flow has been changed by land reclamation and embankment. The medieval Thames was twice as wide, and peppered with now-vanished islands.

Today, we can even stop the tide at the press of a button, thanks to the Thames Barrier.

But could we make more radical changes to the Thames, and even divert its flow? Strange though the idea sounds, it has been considered on more than one occasion.

The Isle of Dogs bypass

The earliest suggestion for adjusting the Thames came in 1796. At the time, central London was still a major draw for commercial vessels. Thousands of ships would navigate into the Pool of London each year. Their progress was considerably slowed by the curvy nature of the Thames around Greenwich and the Isle of Dogs. It wasn't just the distance. This was an age before engines. You don't need to be Long John Silver to imagine the challenge of sailing first north, then south, then north again, all while heading steadily west, by the power of wind alone.

The simple solution was to drive a channel through these chicanes, providing a direct east-west route for shipping.

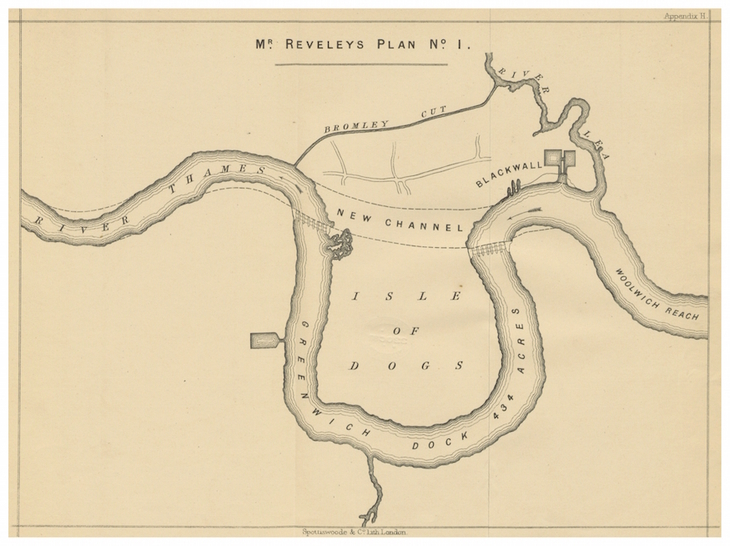

The plan above shows a scheme by architect Willey Reveley. The plan would have driven a new channel between Blackwall and Limehouse, cutting out the bend. Were the channel to magically appear today, both the Museum of London Docklands and One Canada Square would be inundated.

The plans had merit beyond the provision of a quicker route. As noted on the illustration, the cut-off loop of Thames could be converted into a new dock, occupying some 434 acres. This part of London would have been utterly transformed.

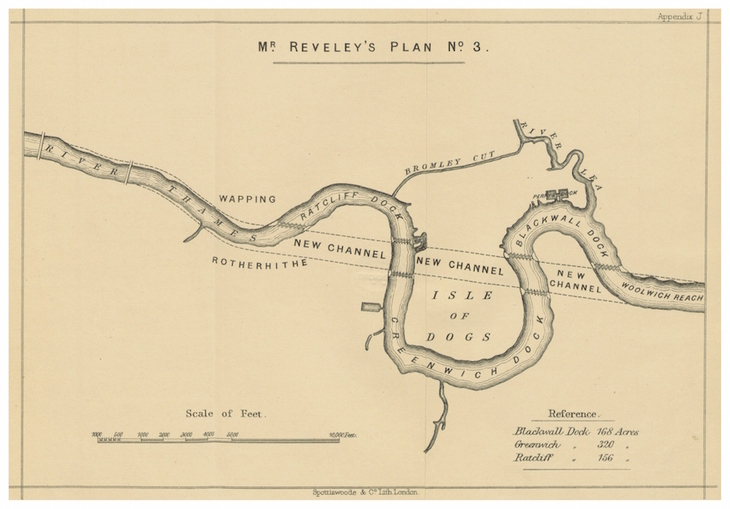

Reveley provided three alternative plans. Perhaps the most ambitious would have created three new docks.

Much of Rotherhithe, Millwall and North Greenwich would have been submerged beneath this plan. The huge cost and engineering challenge of excavating such a trench — with little more than spades and human muscle power to do it — ensured that Willey Reveley's plans were rejected by the government.

The Thames Through Peckham

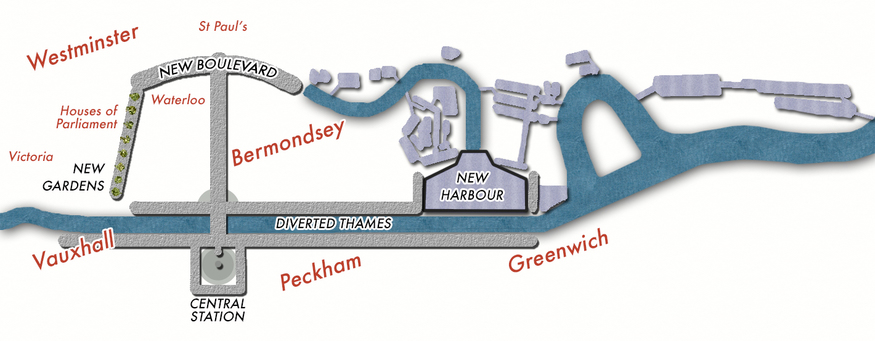

An even bolder plan was suggested in 1933 by another 'Will', the architect William Walcot. His unique idea was to shift the Thames a couple of miles south to run through Peckham. Yes, Peckham.

Walcot wanted to free up space in central London to help ease the growing traffic congestion. The Thames would be pinched off near Vauxhall and Tower Bridge, and diverted through south London. Meanwhile, the old river bed would be turned into a multi-lane boulevard, with pleasure gardens running alongside the Houses of Parliament. Giant roundabouts would be built where today you would find Tate Modern and the Royal Festival Hall.

Walcot's vision also included a monumental new harbour at Deptford and a grand Central Station to replace Victoria, Waterloo and London Bridge. Kennington would have been the capital's chief rail hub, complete with rooftop aerodrome.

The vast cost of realising such a scheme once again ensured that it never moved beyond the status of 'vision'. Setting aside the unprecedented engineering challenge, imagine the thousands of homes, offices and historic buildings that would have to meet the bulldozer.

As far as we're aware, no serious plans to divert the Thames have been floated in recent years. The idea of re-engineering such an important river seems fanciful, even hubristic. But you never know.

With the challenges of global warming and the threat of rising sea levels, perhaps our not-so-distant descendants will look again at ways to relocate the river. Perhaps, in a car-less future, the great Thames might be split into three streams, running still through central London, but also burrowing along the routes of the North and South Circulars. Or maybe the city centre will be abandoned to the rising seas, and the river will once again be allowed to swell to its natural width. Only time and tide will tell.

Secret Rivers exhibition runs at the Museum of London Docklands until 27 October 2019. The nearest station is West India Quay (DLR). Entrance is free. Read our review here.