For more of all things London history, sign up for our new (free) newsletter and community: Londonist: Time Machine.

"The whole palace was like a burning coal, and vomiting up fire at a rate that would have done credit to Vesuvius."

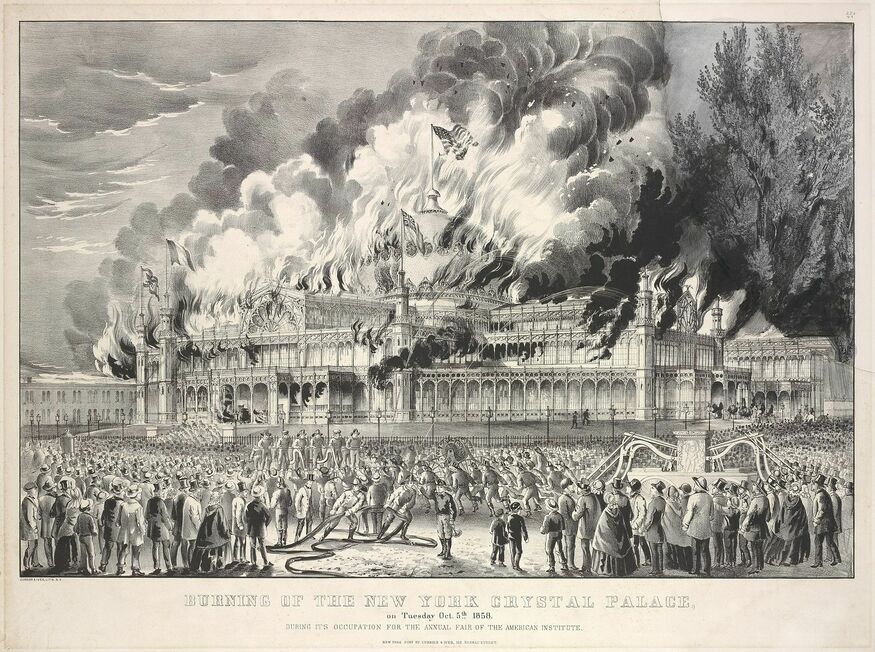

Onlookers watched aghast as the Crystal Palace — a glassy symbol of all that was great with the country — went up in smoke. "The fire spread in every direction," reported one newspaper, "and in a little over twenty minutes from the time when it was first discovered the entire roof of the place fell, carrying with it most of the walls beneath." It's a well-documented London conflagration — up there with the Great Fire of London.

Except that this was 1858. In New York City.

They say imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, so London must have felt pretty proud of itself when, on 14 July 1853, a 'Crystal Palace', constructed from glass and iron in the form of a Greek cross, was inaugurated where Manhattan's Bryant Park stands today, as part of the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations. Though the stateside Crystal Palace borrowed heavily from Joseph Paxton's original design, it wasn't identical. Notably, the American cover version was crowned with a dome 30m in diameter, a Star-Spangled Banner fluttering away at the top. (Whether the dome design itself was pinched from Brighton Pavilion, we'll leave to you to decide.) Anyway, the Crystal Palace was a big deal in New York, with Franklin Pierce, then-President of the United States, speaking at the opening ceremony.

If you were splitting hairs, you could say that the Americans had a Crystal Palace BEFORE the Brits; while the original Crystal Palace in Hyde Park was officially called the Great Exhibition, its nickname (derived from Punch magazine referring to it as a "palace of very crystal") would only become official when the building reopened in Sydenham in June 1854 — almost a year after the New Yorkers had opened theirs. But we digress.

Hyde Park's Great Exhibition had predominantly been one big showboating sesh for the British Empire, yet the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations — as its name suggests — showed off creations from around the globe. That included Italian pantings and sculptures, beautifully-carved Austrian furniture, and a 14-foot carpet woven by women from Canada. Among American additions was a bronze statue of George Washington on horseback, while the Anglophilic accoutrements featured suits of armour loaned from the Tower of London, a miniature tea service made from a single dime, and a portrait of Queen Victorian woven from wool. How very quaint. There was also a scale model of London's Crystal Palace; a nice little Easter egg.

Neighbouring the New York Crystal Palace was the Latting Observatory (named for Waring Latting, the man who conceived it). This pointy, iron-braced wooden tower — with its views reaching as far as Queens, Staten Island and New Jersey — was briefly the tallest structure in New York City. And here, the Americans can proudly claim to themselves have inspired a European icon; no not the Shard, but the Eiffel Tower, which took its cue directly from Latting's structure.

Speaking of heights, the American industrialist Elisha Otis chose New York's Crystal Palace to demonstrate his free-fall safety elevator, personally riding it up and down, then occasionally cutting the hoisting rope while at a knee-trembling apogee, and shouting "All safe, gentlemen, all safe!". He might've been put up to these dramatics by P.T Barnum no less, who'd been called in to give the venue fresh life, after its commercial viability started flagging early on.

Otis's success is measured in the fact that you still see his name on the inside of lifts internationally now. Alas, New York's Crystal Palace itself wasn't to prove so enduring.

We would say that New York's Crystal Palace went so far in its imitation of London's, that it even followed suit when it burned down — expect that the Americans' Crystal Palace was levelled by fire just five years after it opened, in October 1858. The fire broke out in the lumber room (which seems a likely place for a fire to start): "The flames spread with fearful rapidity..." wrote one publication, noting how the palace and its contents were destroyed in no time. Early accounts wrote that many people were killed in the blaze, although miraculously, it appears that no one actually was — despite around 2,000 being inside at the time. If you're wondering what happened to the Latting Observatory, that had already burned down two years previous.

London's own Crystal Palace would subsequently suffer from two major fires: one in 1866, that destroyed the North Transept, and another in 1936, which was the end of it altogether. If only there'd been a third Crystal Palace built somewhere in the world, perhaps we'd still have it now.