A guide to the Thames Tideway Tunnel, London's new supersewer.

Tell me, in 50 words or fewer, what this supersewer is?

It's a huge new interceptor sewer, directly under the Thames. The existing sewers don't have enough capacity to cope with demand during downpours. Feculent water is often ejected into the Thames. Soon, it'll pour into this new tunnel, whose gentle slope will carry it east towards Beckton for treatment.

So this will finally end the problem of sewage getting into the Thames?

Almost, but not quite. The supersewer is designed to handle over 95% of all discharge. On rare, diluvial occasions, some sewage will still escape into the river. However, the supersewer will have captured the most harmful "first flush" portion of the excess, and any foul water entering the Thames will be more diluted than current discharges.

What route is this new sewer taking?

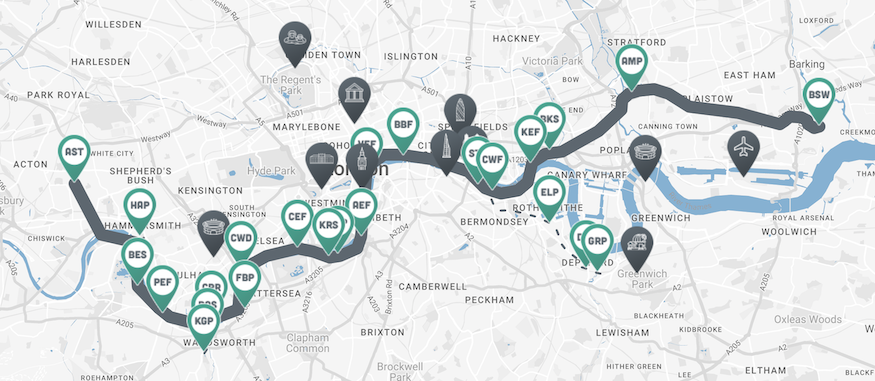

The supersewer begins at Acton's existing storm tanks. After heading south through Chiswick, it reaches the river just west of Hammersmith, then follows the Thames as far as the Rotherhithe tunnel. It then follows the Limehouse Cut towards Abbey Mills, and thence to Beckton for treatment. Tideway have put together an excellent interactive map that gives details and visuals of all the key sites along the route.

Throw some vital statistics at me

Length: 25km-long (15.5 mile). That's like walking in a straight line from Tottenham to Croydon.

Depth: 67m at its deepest. That just happens to be the same as the deepest point on the underground (near Hampstead).

Diameter: 7.2m (about three double-decker widths and a whole metre wider than a Crossrail tunnel.

Construction time: Eight years, involving 20,000 people.

Amount of sewage flowing into the Thames annually: 39 million tonnes.

Who's building it?

The tunnel is being built by Bazalgette Tunnel Ltd, who trade as Tideway. This is why it's sometimes called the Tideway Tunnel. Tideway are building the tunnel on behalf of Thames Water, backed by a financial consortium.

Six tunnel boring machines (TBMs) were set loose through the London clay (west) and chalk (east). Four of these dug out the main tunnels, while two smaller TBMs handled two connecting tunnels at Greenwich and Wandsworth. As per tradition, the six machines were named after women, with a public vote choosing the dedicatees: Rachel Parsons, Audrey 'Ursula' Smith, Millicent Fawcett, Charlotte Despard, Selina Fox and Annie Scott Dill Russell.

Tunnelling was completed in April 2022, and most of the additional engineering is now complete.

When will the Supersewer open (if that's the right word)?

The planned opening date is some time in the first half of 2025. The original plan was to open in 2023, but engineering work was held back by Covid restrictions.

You might wonder why, if most of the engineering is now complete, the sewer can't open much sooner than 2025. The reason is testing. Just like a railway, the sewer must be tested under controlled conditions before it is brought into full service. Unlike a railway, the testing regime can't be done to a precise timetable. It needs heavy rainfall, which can't be predicted far in advance.

How much is this costing? And who's paying?

The current estimate is £4.5 billion, up considerably from the 2014 estimate of £3.52 billion. The money is coming from your water bill (if you're a Thames Water customer). 15 million households are paying roughly £20-£25 per year to fund the project.

Why do we need a supersewer?

Tens of millions of tons of sewage go into the Thames each year. This is self-evidently awful.

We all know the story of Joseph Bazalgette's Victorian sewers — built in Victorian times to save the capital from its own waste and relieve the 'Great Stink'. Bazalgette future-proofed his system by building it larger than strictly necessary. But 150 years on, the population has more than doubled, and we've massively ramped up our water use.

At the same time, much more of London is now paved and tarmacked over (including lots of front 'gardens' that have been paved over to hold cars). When it rains, the lack of permeable surfaces creates far more run-off into drains than the Victorians had to deal with. And heavy rains are all the more likely as the climate slowly warms.

All of this means that the existing sewer system is full to capacity whenever we get a sustained period of rain. With nowhere else to go, the waste water must be discharged into the Thames. If it were not, it would back up into our streets and homes, which would also be self-evidently awful.

The new sewer is at a lower level than the existing sewers, and will take on almost all of the excess. This will greatly improve water quality in the Thames, which is obviously good for both wildlife and human activity.

Did anyone object?

Well, of course. This is a huge undertaking. Any project that costs so much money and takes so much time should, quite rightly, be scrutinised and held to account at every stage. And that scrutiny found much to challenge. Complaints ranged from the financing model, to the years-long disruption at work sites.

Some argued that the whole approach was wrong, and that sewage discharge should be reduced by a 'green infrastructure' approach. This would, for example, strive to increase permeable surfaces (encourage Londoners to dig up all those paved drives!), install green roofs and collect rainfall in water butts. Such an approach would have further benefits, like increasing biodiversity, reducing air pollution and simply looking nicer. Indeed, it would make London a better place if we can do much more of this kind of thing, even with the super-sewer handling most of the run-off.

What'll we see above ground?

Not all the action is going on deep beneath the river. The project will also create seven small parks and public spaces at some of the access sites along the river. The most prominent and sizeable is in the City, where a new chunk of embankment is under construction just west of Blackfriars Bridge. Others are being constructed at Putney, Chelsea (covering up the old mouth of the River Westbourne), Vauxhall (beside MI6, shown above), next to HMS Belfast, Convoys Wharf and King Edward Memorial Park near Wapping.

What happened to all the excavated soil?

London has a long tradition of reusing excavated earth for other means. The spoil from St Katharine Docks, for example, was taken upriver to level out Battersea Park; the Crossrail dig provided earth to improve a nature reserve at Wallasea Island in Essex. The Tideway Tunnel project has also put its scoopage to good use. Chalk and clay excavated from the tunnels was transported to Rainham, to make improvements to the RSPB nature reserve.

Will the well-publicised problems at Thames Water affect the Supersewer?

The project is so near completion that it's unlikely to be jeopardised by the financial difficulties at Thames Water. As already noted, construction and delivery of the sewer is being undertaken by Tideway, which is an independent company working on Thames's behalf. Tideway is financed by a consortium of investors, to be paid back later by Thames Water. So, even if Thames Water goes into administration (and that's now looking less likely), Tideway could still complete the work if the Government (who would take over as last resort) continued to pay for the work. Delays can't be entirely ruled out, however.