Where have you been? Where are you going? What are you doing?

Three prescient questions when slogging alongside a main road on a Thursday morning in the unplumbed depths of Beckenham — searching for somewhere only really familiar to us from the unsettling lore of London's past.

The Bethlem Royal Hospital is where moneyed women crow at the afflicted from behind their hand fans, in the denouement to William Hogarth's A Rake's Progress. The backdrop to a creaky horror B-movie starring Boris Karloff. The place that gave birth to the word 'bedlam' — 'a scene of uproar and confusion'. But here's the thing —Bethlem still exists, and its nothing like any of the above.

The hospital began life in 1247 in what we now know as Bishopsgate — although wasn't treating the 'insane' until sometime in the 14th century. It shifted about in central London, denounced by one commentator as "a crazy carcass with no wall still vertical – a veritable Hogarthian auto-satire". But though the hospital's early centuries of patient care perhaps weren't squeaky clean, its reputation grew to be more demonised than it deserved. Bethlem moved out here to the fringes of Croydon in 1930, where it continues to treat people (these days referred to as 'service users'). Its setting, in the peaceful pastures of Monks Orchard, is a calm oasis that feels worlds away from the clamorous road that takes you here.

There is very little Hogarthian about Bethlem now. Inescapably, there are the grotesque sculptures of 'Melancholy' and 'Madness', flanking the staircase up to Bethlem Museum of the Mind, situated in a grand administration building, and the place we have come here to see. The tortured Portland stone characters once strained at their manacles above Bethlem's gateposts in its Moorfields days, and can only have stirred further dread and paranoia into the latest hospital admissions. Both inspired figures in Hogarth's work entitled Madhouse.

There are collection boxes, too, from times when it was standard practise for the public to come and view utter strangers — sometimes as they endured immense stress, pain and humiliation. But as the museum points out, not everyone came here to leer and laugh; many pitied Bethlem's ill, gave alms, and tried to understand what they were feeling.

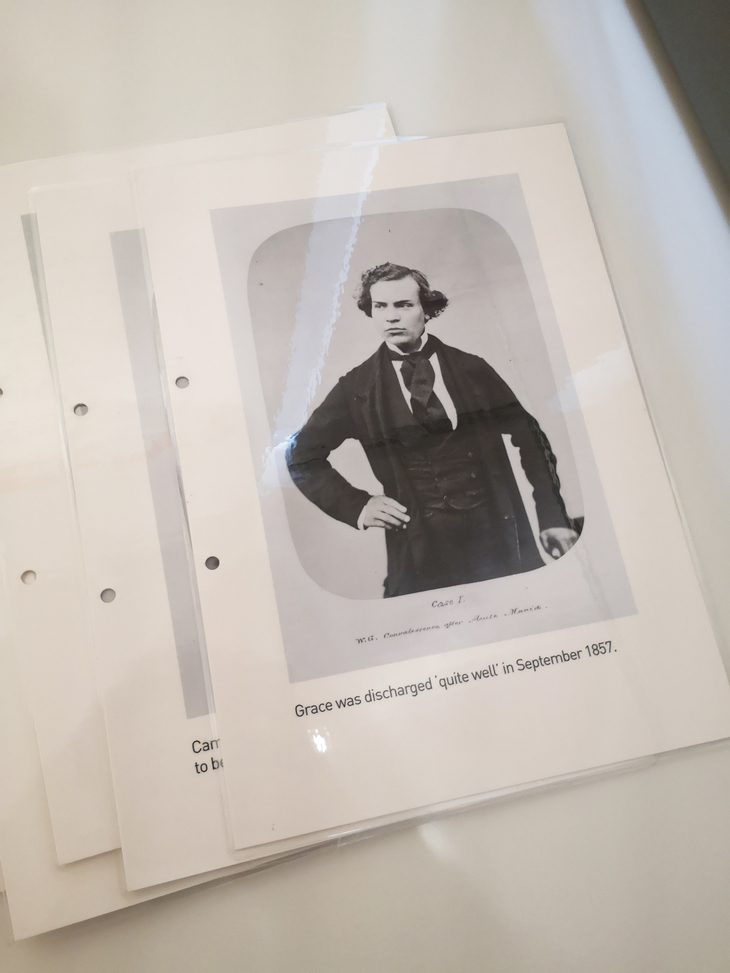

Bethlem Museum of the Mind is a candid recollection of the institution's past, but also an engrossing exploration of psychiatric health as a whole. Henry Hering's photographs capture Bethlem patients on their arrival, and again just before being discharged. If, of course, they were discharged. In 1857, the hospital claimed only to have a 57% 'recovery rate'. A despairing letter from 1892, written by the wife of one former patient, explains to a Bethlem doctor that her husband had been doing "so much better latterly" but was recently found drowned in a brook, suicide presumed.

Correspondences like this display trust, affection and bonds between doctors and patients; something you might not consider, even in stoic Victorian England. But the museum doesn't demur from past treatment of patients that we now balk at. James (William) Norris was detained at Bethlem for over a decade in a brutal cage of harnesses and bars. When it came to public light, the scandal went national, prompting electoral reform and the 1815 House of Commons Select Committee on Madhouses. (The transposing use of language and words like 'mad', 'looney', bonkers', 'gaga' and 'berserk' is also touched on. Interesting how some have been reclaimed for positive use.)

Elsewhere a case of pharmacy jars, once containing nitric and hydrochloric acid, glows an ominous green. There is a horrifying, Frankenstein-like, quality to them. But then the use of chemicals for depression, anxiety and other mental health issues is still much debated. Should medicines be prescribed against people's will at all? We've made great leaps in understanding mental wellbeing, but there's a lot of work to come. That message is repeated over and over here.

And there are some surprising discoveries. 'Electro-shock' treatment (or electroconvulsive therapy, to use its proper name) might conjure up memories of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. A clunky old machine with 'A.C Volts' dial on display only compounds the stereotype. Yet a recent BBC documentary on display talks to patients who swear by the treatment as a kind of 'topping up' of the soul. The late Carrie Fisher felt she benefitted from the treatment so much, she called one of her autobiographies Shockaholic.

The museum explores both lows and highs of life with mental health disorders. Tales of woe and heartache rub shoulders with those of coming to terms with diagnoses, managing to live full lives again. This spectrum from despair to hope is reflected in the museum's design too. So while one corner is fitted out, rather terrifyingly, with the inside of a padded cell from St Bernard's Hospital in Ealing, the space also features floor-to-ceiling windows, looking out over the verdant grounds here at Monks Orchard. Sit on the wicker chair, and see Bethlem's present day service users strolling over the grass.

In fact, patients past and present are an inherent cog in the museum. Not only do service users often visit this space, they help create it. Eclectic displays of art show how patients have often used the canvas to seek solace, or even just to vent. Lucy Macleod's 2003 work AAAR is a cartoonish scream on a five pound note. Welcome to My Psychosis by 'Figgy Fox' throbs with colourful, comical overtones, but in a nightmarish scenario of severed hands and nuclear explosions. Sometimes you don't know whether to laugh or cry, and that's when you start to get a feeling for how every single day is like for some people with certain mental health issues.

When you consider it, this place is as much art gallery as it is museum; indeed downstairs, the Bethlem Gallery operates as a working space where service users come to be creative. On our visit, a series of gelli plate pieces explore the thoughts and emotions of people from the Mother and Baby unit. The tools used to create these visions of life before and after children are on display too, and the everydayness of these forks, combs and tooth brushes hints at the prevalence of mental illness. Even if you're fortunate enough not to experience it, you'll know plenty of people who will. That's why this museum is such essential viewing.

The Museum of the Mind poses a tumult of questions and doesn't pretend to have all the answers — not even half of them. But just like Bethlem Hospital, it is a living, breathing thing — candidly looking back over its shoulder; learning and progressing every day. For all those images we have of 'Bedlam' as a cruel 'looney bin', 'madhouse' or other such slurs, in 2020, it's quite the opposite. This is somewhere to pause, think, focus and reflect.

Bethlem Museum of the Mind, Bethlem Royal Hospital, Monks Orchard Road, Beckenham BR3 3BX. Open Wednesday-Friday except public holidays and the first and last Saturday of the month. Pre-booked groups Monday-Tuesday. Entry is free