London's shortest-lived theatre — the Royal Brunswick in Shadwell — lasted just three days. It collapsed on 28 February 1828, killing at least 10. Jennie Pollock, a descendant of one of the rescuers, recounts the tragedy, and shares evidence from her ancestor that the death toll may have been higher.

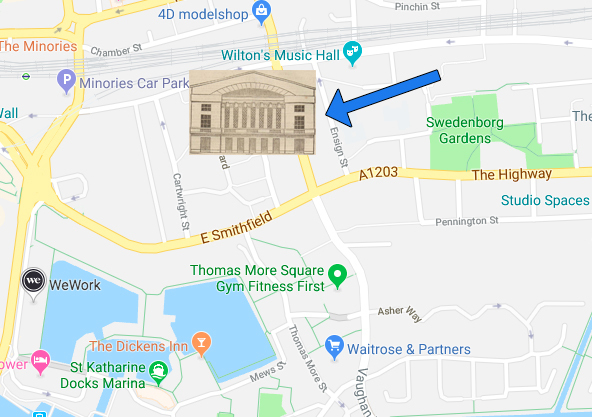

The Royal Brunswick Theatre, near what is now Wilton's Music Hall in Wellclose Square, was full of life on the morning of Thursday 28 February 1828. It had just opened that week, and actors, set designers, musicians, costumiers and more were gathered to rehearse in their vast new playhouse.

“All”, reports a certain Mr Charles Dickens, “was cheerful bustle, hope, and excitement”.

A little after 11.30am, a series of crashes was heard from the upper levels. No one paid much attention – although it had been open since Monday, the building wasn’t 100% completed. Carpenters were still finishing up the roof supports, as well as making sets and props.

The ominous rumble that followed, however, was unusual, and without further ado the roof collapsed upon the whole company.

A local clergyman, the Revd GC Smith, was at his church nearby and ran to help. “The scene was tremendously awful,” he recounted later. “The whole of this immense pile of building, which had resounded a minute before with the preparations for amusement and gaiety, was now a heap of ruins, destruction and death.”

A tornado of girders, bricks, and timbers

While the disaster was a shock, to many people it was not a surprise. There had been concern over the rush to put a heavy, iron roof (a fairly new invention) on before the mortar was properly set.

The walls had a pronounced buckle, and an iron bar had fallen, causing it to drop a couple of inches. As Dickens puts it, “a vague sense of danger had filled the minds of every one connected with it, except the proprietors: who were too eager for profits to listen to anything that might cause delay.”

It is unclear whether any specific incident precipitated the roof’s eventual collapse, but collapse it did, in “a tornado of girders, bricks, and timbers.”

There were some miraculous escapes and several acts of great bravery among the rescuers, but there came a point when mere hand tools were unequal to the task of freeing those trapped beneath the iron girders, or retrieving the bodies of the dead.

A new eye-witness account

And here’s where my interest in the story begins. Not far away (see map above), St Katharine Docks were under construction. Word was sent, and all the men who could be spared came to apply their skills to the task. One of those labourers was my great-great-great grandfather, Robert Pollock.

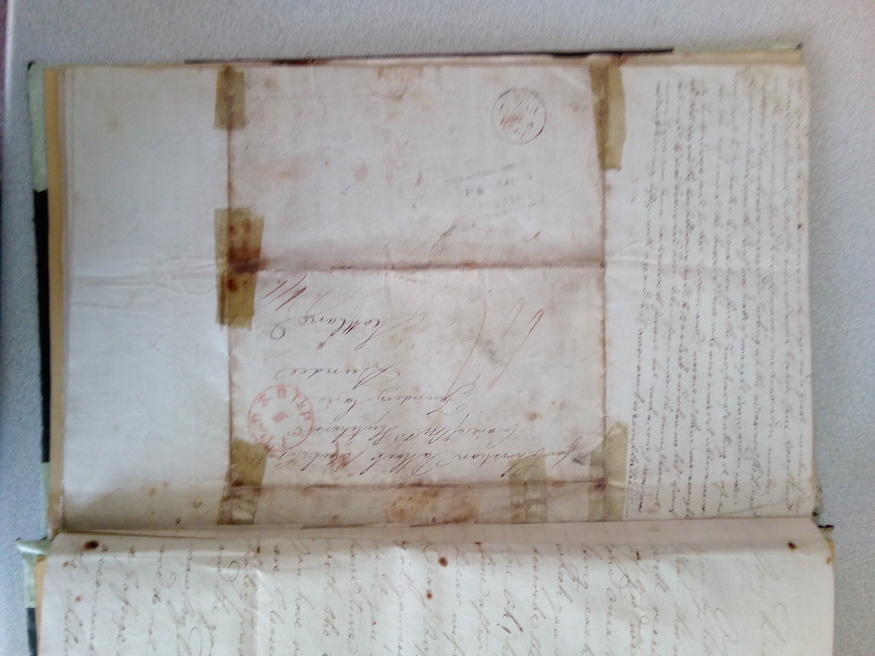

Robert had moved to London from Dundee to seek work, leaving his wife and two small children to follow when he had got established. He had written a letter home on 28 February, but hadn’t yet posted it when he was called to the disaster. Here’s his postscript about the incident, transcribed by my dad, with original spellings and (lack of) punctuation retained:

"a most serious accident has happened in London on the 28 th of february by the falling in of the roof of the New Brunswick theatere it happened at 12 oclock in the forenoon when they were preparing for a play that night, and while the play actors were on the stage and a great number of men at work in different parts of the house and awful to report those smothered in the ruins are supposed to be upporwards of one hundred in number. I was one of those who were engaged in picking up the remains of the Dead the reason of which was the Rooff was made of wrought iron and an order was sent to my Master to send men for the purpose of cutting it up so that they might come upon the bodies of those who were under it."

"Upperwards of a hundred were sent for that purpose and I was one of them. We wrought all that day and the two following nights to 12 oclock and when we left off work last night 16 of the dead bodies had been taken from under the ruins. I have not room to give you more particulars at present but such a scene I never was wittness to in my life. - with regards to it ower work is completed."

Estimates of the dead range from 11 to Robert’s 16, and it seems as though around twenty were seriously injured. With a seating capacity of around 2,000 in the auditorium, though, it is a good thing the theatre didn’t collapse during a performance, or its death toll would have been much, much higher.

An inquest was held, and its verdict was 'Accidental death by the fall of the roof of the Brunswick Theatre, which was occasioned in consequence of hanging heavy weights thereto'. The two proprietors (one of whom had died in the incident) were fined 40 shillings – two pounds – each.

Compare this to the £750 raised in subscriptions for the injured and bereaved, and you can see what a laughable rap over the knuckles it was, for men whose 'highly reprehensible' actions were directly or indirectly responsible for the catastrophe.

The theatre was never rebuilt. Today, the site on Enfield Street is occupied by a row of residential properties. There are no plaques recalling this awful tragedy but, if you look closely, you can still find a ghost of the Royal Brunswick Theatre. A row of bollards stretches the length of the facade, and each is marked RBT.

See also: A map of every London disaster to claim at least five lives, and further forgotten disasters in this series.