If rats do not hold a place in the affections of Londoners, they certainly have a place in our city's history.

Rats the size of cats persist in urban mythology. Rats are revolting, cannibalism being only one of their horrible habits. But, as you'll see, they have their uses too. We'll try not to gross you out too much with our rodentine review.

Pro rata

Compared to many other nations, we have an unusual richness of records. Some of the government archive, happily, was moved out of the Palace of Westminster just a few years before the bulk of the building burnt down in 1834. Yet the backup warehouse used — an old stable no less — was so damp that records stuck together or turned to putrid sludge attractive to vermin.

One of the early jobs of Sir Henry Cole — who later masterminded the Great Exhibition of 1851 — was to serve in the Records Commission. Various Records Commissions had sat pondering the preservation of records for nearly 40 years from 1800. A dramatic gesture was called for. Cole brandished a dead rat (one of several found in the store) as evidence of the state of the public records. The direct result was the creation of the Public Records Office (PRO) — and now the bright and shiny National Archives at Kew. Request file number E 163/24/31 and you will be brought a dead rat, the very one brandished by Henry Cole.

Right royal rat

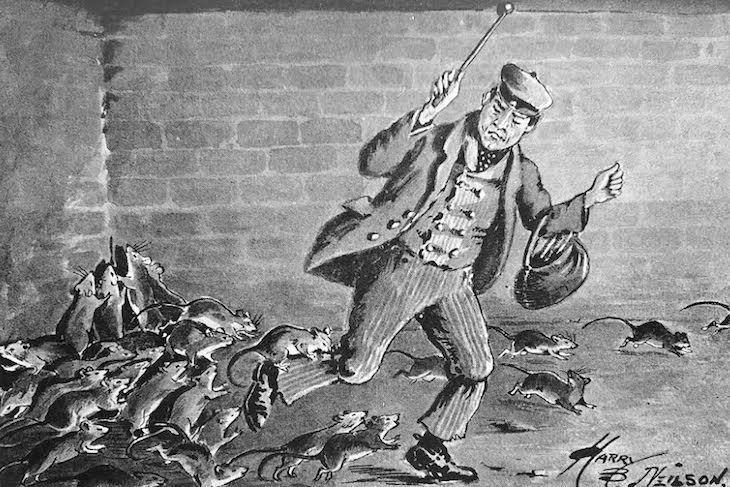

The producers of the TV series Victoria crammed in as much period colour as they could, even including some rats. In one episode, the pests were displaced from their dens by the installation of gas pipes at Buckingham Palace and the royal ratter made his appearance. Thanks to Victorian journalist Henry Mayhew we know something of him. His name was Jack Black.

Women more particularly shuddered when they beheld him place some half-dozen of the dusty-looking brutes within his shirt next his skin; and men swore the animals had been tamed, as he let them run up his arms like squirrels, and the people gathered round beheld them sitting on his shoulders cleaning their faces with their front-paws, or rising up on their hind legs like little kangaroos, and sniffing about his ears and cheeks.

But those who knew Mr. Black better, were well aware that the animals he took up in his hand were as wild as any of the rats in the sewers of London, and that the only mystery in the exhibition was that of a man having courage enough to undertake the work.

Mr. Black informed me in secret that he had often, "unbeknown to his wife," tasted what cooked rats were like, and he asserted that they were as moist as rabbits, and quite as nice.

Hair today, gone tomorrow

Frank Buckland in his Curiosities of Natural History (1857) devoted a whole chapter to rats. Here is one of his curiosities:

The love of warmth brings many rats out of the sewers to take their siestas in the large hair warehouses in Lambeth. They only come in the day, and decamp at night, probably in quest of food. They have made runs up on to the floors where the hair is placed to dry, and, finding a nice soft bit, roll themselves up quite into a ball; the outside of which is horse-hair, the nucleus a live rat. The boys connected with the establishment have found this out, and go feeling among the hair with their hands. The moment they come on a lump harder than the rest, they pounce upon it without fear, for the rat cannot bite through his thick self-made great-coat: they then rush off to a tub of water and shake poor Mr. Rat out of his hairy (not downy) bed into the merciless element, when he is soon drowned.

Rats with a cover story

In the second world war, rat skins served as clothing for small explosive devices and a crate-full was made by the British Special Operations Executive and sent to France. It seems that the box was captured by the Nazis and, although the crate failed to explode, they subsequently wasted a lot of time being overly-suspicious about any dead rats they came across.

The rats even had a cover story. Those catching and donating rats to the SOE were not told they were going to be used for sabotage, but that they were assisting medical research at London University.

Keep the home fires burning

Here are some nibblings from the splendidly named Willoughby Mason Willoughby in his annual report of the Medical Officer of Health for the Port of London in 1917.

Two Plague-infected ships [Sardinia and Matiana both calling at Bombay] were dealt with on arrival in the Port.

Arriving ships were routinely inspected at Gravesend and the surviving plague cases were removed to hospital, the dead having already been buried at sea.

A small and localized Plague infection among rats in the Royal Albert Dock, which had been found in the course of rat examination late in 1916, terminated early in the year. The routine rat examination has been steadily carried out throughout the district...’

2,918 rats — mostly brown rats — were examined throughout the Port of London in 1917 and two were found to be infected with the plague.

A small hut... in constant use by dock men, was noticed to be over and under run by rats; its walls of wood were doubled and originally filled with sawdust — primitive insulation affording, with the fire kept burning for cooking purposes in the hut, comfort to both man and rodent. A sick rat, which was subsequently found to be plague-infected, was killed within a few feet of this shed on 6th November, 1916. On fumigating the shed with sulphur dioxide and opening up the floor, a few rats in a state of putrefaction were found. The shelter was again fumigated and put out of use. The close association of infected rats and human beings… had been a dangerous condition.’

Where to see rats in London

Such spots might not make it on to everyone’s bucket list and, unless you want to catch leptospiral jaundice, we really don’t think we should encourage you. (We hope the skittering horde we once encountered by the canal off Lisson Grove is now under control!) Anyway, on a happier note, plague rat toys for people are available here and for cats are available here. There are museums that have mummified rats in their collections, though possibly not in pride of place. These include the Museum of London in Docklands, Sir John Soane’s Museum, Fulham Palace and, of course, the National Archives.