Pulling into the sleepy train station of Knockholt in Kent, you can see how it inspired Edith Nesbitt — who lived nearby — to set her children's classic, The Railway Children, here. There is no Bernard Cribbins lookalike to greet us today, just a car park jammed with commuters' hatchbacks, and an Oyster tap in station, clues to the proximity of Knockholt to London.

Knockholt was once even closer to London though — in fact from 1965-9, it was part of London, which is what we're here to learn more about.

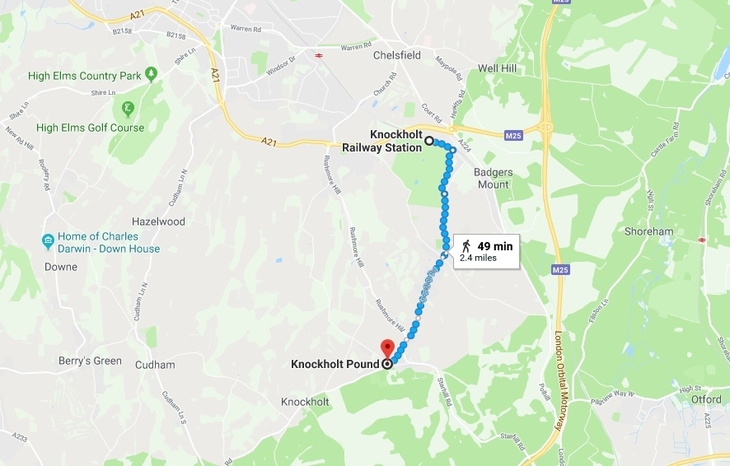

First though, another conundrum: Knockholt station is not in Knockholt. As the crow flies, it's a good two miles away. Things are certainly confusing in these parts.

It's all Essex's fault. The station we've just alighted at is actually in the village of Halstead; but there's a Halstead station in Essex too, and due to the number of Victorian passengers getting their top hats and bonnets in a twist, as they turned up at the wrong Halstead, this station became Knockholt.

Being the non-car-owning city snowflakes we are, there's a good two-and-a-half-mile tramp ahead of us.

Fortunately, it's a crisp enough winter's afternoon, and golden sunlight falls along the route of winding country lanes lined with the remnants of autumn leaves, a woodland-shrouded golf course, and a farm, where a small herd of cud-chewing cows stare at us as if to say 'you do realise there are no paths around here mate?'

We wend through the picturesque village of Halstead, with its hobbit-like flint cottages and crooked chimney stacks (there's more crookedness than first meets the eye: apparently shamed former Sun editor Kelvin MacKenzie frequented the local boozer here).

The lingering redolence of Fleet Street ghosts aside, this rural idyll feels a world away from the clattering metropolis of London. So how was it that Knockholt — the village we're about to stroll into — ever ended up in London in the first place?

It all started in 1929, when the Bromley Rural District Council — of which Knockholt was a part — applied to be converted into an Urban District. As David Smithers writes in A History of Knockholt in the County of Kent, the local consensus was:

That the interests of the inhabitants of Knockholt would be best served if they remained under a Rural District Council.

This wasn't to be, though. For decades, many of Knockholt's inhabitants gritted their teeth; Smithers mentions a village meeting in April 1956, in which the urban designation was again contested, again fruitlessly. "The people of Knockholt have... been steadfast in their determination to opt out of the London area for many years," the Liberal MP for Orpington, Eric Lubbock, later acknowledged.

More was to come. The implementation of The London Government Act on 1 April 1965, came as a cruel April Fool's to many of the Knockholt villagers. Now, this picturesque setting — with its scattering of dairy farms and handful of village shops and pubs — was a suburb of one of the world's largest cities.

We arrive in the distinctly un-urban centre of Knockholt, known as The Pound. The name is fitting given the area's affluence (stately piles are set into the surrounding fields and hills, including Chevening House, currently the nominated digs of the foreign secretary). Grand houses — some follies, some Kent clapboard beauties — abound, and what is apparently Britain's largest oak framed building, resides in the village too. 'Pound' in this case, though, refers to where livestock was kept, until the 1930s.

Scanning the scene, we pick out but a brace of London icons — a black cab parked up in a driveway, and a red phone box, enterprisingly turned into a walk-in defibrillator. You can't help but think this hints at the average age of the local.

But all that's changing.

"We lived in London, and after our second break-in, we thought we'd get out." says Tony Slinn, Knockholt local, enthusiast, and chairman of the Knockholt Society.

"One, this has a nearby railway station; two, it was next to the M25, which they were starting to build." Rural Knockholt may be, but it's well connected, especially if you have a car. (In the time you can walk from Knockholt to the station, you can get from Knockholt station to Charing Cross.)

Tony and his wife Sandy have lived here for 30 years — eager to put down roots, and assume the responsibilities of village life, including help organise its impressive bi-annual carnival.

"This is the nearest proper agricultural-based village to London," says Tony, "It's still surrounded by green belt property, has all sorts of protections on it."

But there is a new breed of Knockholter moving in. "They don't stay long," says Sandy Slinn of the younger villagers, who've cottoned on to the commuting benefits of the area, but offer little in the way of community spirit.

"Now there are lines of cars all the way down the road [outside the station], which is making life a nightmare," adds Tony.

That may be the tussle that Knockholt has on its hands right now, but let's return to the 1960s, when the village was in the midst of its fight to re-ruralize.

Peter and Betty Hinton — a town planner and architect respectively — moved to Knockholt in 1967, while the village was still in the borough of Bromley. Betty, originally from Woolwich, remembers just how incongruous the village felt to its London status back then, "I didn't go out between 12 o' clock and one o' clock, because that's when the cows went onto the roads. They were huge. And to have one of those things sitting next to your car... I can assure you I didn't like it much at all."

Still, she and her husband fell in love with the place. Building a house he'd designed on Knockholt's Pound Lane, Peter remembers getting permission from Bromley council, so that he could use the bricks he wanted. By the time the house was finished, it was in Sevenoaks. "He was a very slow builder," laughs Peter.

What do they remember of the fight to put Knockholt back under Sevenoaks' jurisdiction at the time? And why did they want it so badly?

"I think it was a status thing," says Peter, "That Kent was more countrified.

"People came up, getting us to sign things [a petition sent to Parliament overwhelmingly supported Knockholt's transfer to Kent]. I don't think I had any strong opinions at the time, because we were really newcomers.

"But at the time I said to Betty, 'look, no way are they going to win. No way will they move us to Kent'. And of course I had to eat my words.

"I didn't think they had a hope in hell."

Indeed, in December 1967, after Knockholt had endured a long tussle with Bromley Council, the Minister of Housing decided in favour of the village transferring to Sevenoaks, and Kent. It wasn't until April 1969 that this finally happened. Mrs Joan Rogers, chairman of the Residents Association, declared:

In these days it is a great achievement for small village such as Knockholt to fight the entire G.L.C. to do something they consider to be right. I think we should feel proud of ourselves.

Here was a real David and Goliath story, though there were two other Davids: the villages of Farleigh and Hooley wriggled out of Croydon — thanks to The Greater London, Kent and Surrey Order — and back into the rural bosom of Surrey.

But what actually changed when Knockholt was granted its wish?

"The parish council," says Tony, explaining that matters of street lighting, the local playground and hedge cutting are still managed by them. They also supports Knockholt Village Tree Society, providing the village with its own swathe of woodland.

"The councillors were from Knockholt itself, rather than living perhaps miles away," adds Peter.

As for the objectively rugged state of the roads around here, Tony admits the Parish council is less effective, which is why every year, he stands up and asks the incumbent councillor 'when are we going to get our roads resurfaced?'. (We'd like to put in for a few pedestrian paths too.)

So some things would get done quicker with a Bromley council? "I don't know, I doubt it," says Tony. "I don't think there's any money in Bromley either," he laughs.

So there's nothing at all about Knockholt that would be better now, had it remained part of Bromley?

"It seems weird to say it — we would actually have been better off staying in Bromley, because we'd have got Oyster cards, for example, for travel," says Tony. "And we'd have got the Bromley tax rates which are a lot less than they are here, instead of Sevenoaks."

"We should go back really," laughs Sandy.

We sense such words are in jest: "This is very much a village, and it is a community," continues Tony. "The various events that we put on at the village hall, for example are very well attended. At my last look. there were 47 different societies in the village."

Peter agrees: "You can go down the village shop and bump into people. The people here, they don't walk past you. They say 'hello' or 'good morning' or you stroke their dog. It's a very nice atmosphere.

"Whereas you can be in Orpington and walk down the street and nobody even smiles at you."

"Living in Knockholt, you're in the best of both worlds as they say," says Betty. "You've got your rural peace here, and a mile down the road, you've got all the community things that people tend to like."

She continues, "I can assure you, my husband as I know him, after 63 years, he's more country than me. I was born in London and I love being a Londoner."

"He always wanted to live in the country, but the epitome for me would be a flat looking out over Tower Bridge."

You can take the Londoner out of London (their village too) but you can't take London out of them.