How one milk bank is working tirelessly to change the face of human milk banking and breastfeeding forever.

Donating milk for babies is not a recent, unusual or even niche phenomenon.

The practise of 'wet nursing' (children fed at the breast by a friend, family member or stranger) is documented in 4,000 year old Babylonian texts, and today can be seen in the form of informal and unregulated milk sharing between families via social media as well as use of assured, pasteurised donor milk from regulated milk banks.

Milk banks in London

London itself has a proud history of milk banking; it was home to the first one in the UK — Queen Charlotte’s and Chelsea Hospital in west London — which opened in 1939 (30 years after the world's first milk bank in Vienna). This paved the way for post war Britain to embrace the move towards human milk banking, and still operates today.

During this time of increasing interest, milk was collected at home by hand and used fresh within 24 hours or frozen for later use. Alternatively, mothers who had recently given birth were asked by healthcare professionals to directly donate milk to other babies within the hospital.

The process of collection and distribution of human milk at this point was rudimentary, and not subject to the stringent screening and processing guidelines introduced in the 1980s following the global HIV epidemic.

Today, London has four of the UK's 15 milk banks, with a further two in Surrey and Hertfordshire. NHS-run banks provide milk based on doctor assessed clinical need to the most medically vulnerable (often premature) babies on their neonatal units, while their mothers recover and build up their own supply.

But new kid on the block — the independent, not for profit Hearts Milk Bank (HMB) operates under a slightly different model, with a unique aim, and lofty ambitions.

Born out of frustration

Hearts Milk Bank — located in Harpenden, just north of London — exists fundamentally to facilitate and support informed choice for parents in their infant feeding journey. Not everyone wants to use it, but donor milk was rarely presented as an option to parents due to limited supply, and strict clinical criteria within the NHS for its use.

HMB was therefore born out of the founders' frustrations at this limited access to potentially life-saving donor milk both within and external to neonatal wards, as well as a drive to support those in the community who may otherwise have a poorly supported, emotionally upsetting and potentially traumatic breastfeeding experience.

At the time of writing, HMB supplies milk to 53 hospitals and has provided a total of 11,250 litres of fully screened, pasteurised donor milk from around 1,500 donors, to around 10,000 babies.

With mid-blowing figures like that, it's hard to believe anything would be left over, but milk surplus to hospital requirements is made available to families of healthy babies in the community whose parents have experienced a variety of hurdles in their initial infant feeding journey. It's this community provision and support that makes HMB unique.

The long term impact that providing donor human milk has had on families in the mere five years HMB has been operational is hard to quantify, but research coproduced by director of the Human Milk Foundation and milk bank founder Dr Natalie Shenker demonstrates the positive emotional and mental health impact that receiving donor human milk may have on families.

This, along with the well-documented positive impact on the rates of devastating gut disease and decrease in hospital stay for premature babies, as well as increased breastfeeding rates amongst recipients, cements the importance of investing in and developing milk banks.

How does milk get from boob to babe?

"Milk" may conjure up visions of neatly lined up cows in a dairy farm, but of course, milk banks do not involve herds of lactating humans. They rely on the altruistic donations of excess milk by an army of donors; as of August 2022, HMB has recruited around 1,500 donors.

Safety and long term health of babies is at the centre of everything the staff at the milk bank do, which is why all donors are blood sampled before being recruited (this sample is kept for a minimum of 30 years for future disease surveillance).

A donor's responsibilities aren't limited to providing milk; they must also keep meticulous lifestyle and medication records, as well as daily freezer temperature records.

Every drop is golden, and any milk that is excess to the requirements of the donor's own child can be placed in milk bank-supplied sterile containers, and frozen. Once at least two litres is stored at home, collection by a nationwide network of unsung heroes in the shape of volunteer 'blood bikers' from the Service by Emergency Response Volunteers (SERV) charity is arranged.

The frozen milk is transported to the milk bank, and on arrival, the donor-supplied information is scanned to determine the oldest expressed milk in the donation as this defines the "use by date" of that batch.

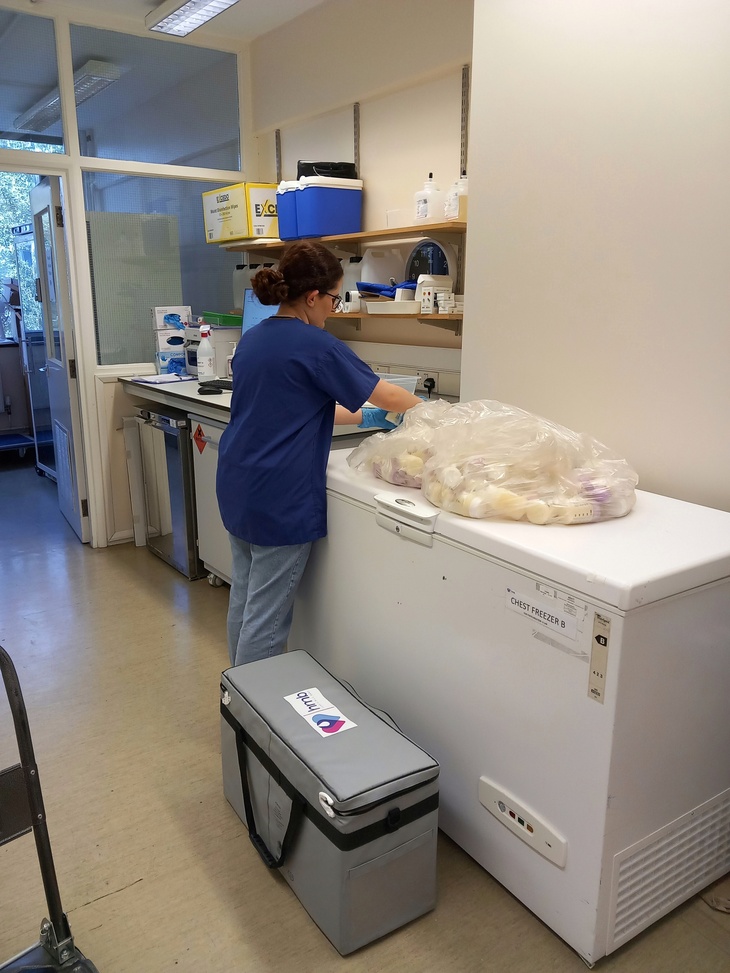

The health and safety of the recipient baby is paramount, therefore the levels of cleanliness in the milk bank are exceptional; staff wear scrubs when handling milk, and boxes of gloves are immediately visible in every room you enter.

Each donation is determined to be either suitable for sick and premature babies, or healthy babies in the community, based on the donor's health and lifestyle records, and the still-frozen milk is thus registered, labelled, and remains frozen until ready to be pasteurised (a form of heat treatment).

Frozen samples are defrosted overnight in a fridge, are filtered, and pre- and post-pasteurisation samples taken to check for bacterial growth and for quality control.

Only after all of these steps can the screened, pasteurised donor milk be labelled and refrozen ready for redistribution.

Once a week, hospital orders are taken and their supply is prioritised, but anything else remaining is documented and distributed to families at home with breastfeeding difficulties.

Much like blood and organ donation, the process is anonymous; neither donor nor recipient is able to find out who the milk has gone to or been received from respectively.

However within the anonymisation process, the milk bank retains full sample traceability, enabling long term protection of public health

More than just milk

A dedicated lactation team supports the usage of donated milk in the community. For many recipients, this is an emotional journey, often based in tragedy or trauma, and the team are acutely aware just how much donations mean.

The team consists of two infant feeding specialist midwives and one lactation consultant who are the first point of contact for recipient families after they have been referred by a medical or lactation professional.

The team fondly recollects all the journeys that have been supported via the use of donor milk, and their office is adorned with photos of families that they have worked with. Emotional gratitude radiates from the smiling faces and chubby baby cheeks in the photos, and although they may never have met in person, it is clear the team feels emotionally connected to every single family. It is an uplifting environment, and recollecting my own difficult journey is met with empathy and kindness — like receiving an "It'll all be ok" hug from a friend.

Each request for donor milk outside of a hospital setting is unique — from mothers with double mastectomies, to trans parents and same sex couples unable to lactate, people with initial feeding difficulties, bereaved fathers and mothers undergoing chemotherapy – the team support them all with the same care and devotion.

For some, receiving the first few days of donor milk is all they need to feel content. For others, a more long term supply is requested. The lactation team ascertains the family's requirements, and support is provided to optimise the mother's lactation where possible, allowing fulfilment of as many requests as the limited community supply allows.

What does the future hold for milk banking?

HMB is at the forefront of research into the infrastructure surrounding milk banking, from storage, modelling future demand, environmental impact and transportation — ensuring longevity and cost efficiency in such future endeavours.

Despite the UK having some of the lowest breast feeding rates in the world — with only 1% exclusively breastfeeding at six months — there is no short supply of women coming forward to donate their milk.

Unfortunately, UK milk banks are limited in both the number of donors they can recruit and the number of families and hospitals they can support, due to facilities, staffing, and lack of ringfenced funding. However, with a predicted increase in demand over the coming years due to expectation of release of national guidelines on use of donor milk in premature babies, HMB is optimistic about its ability to increase recruitment and processing.

Although it is a not-for-profit organisation, and is supported by charitable donations through the Human Milk Foundation, HMB has noble ambitions of providing equitable access to donor human milk for all who require it, be that in the hospital or community, and it believes this may be possible within five to 10 years.

Whatever happens, it looks like London and the surrounding areas are set to remain the centre of the UK milk banking world for a long while yet.

Within London — Guys and St Thomas'; Queen Charlotte's and Chelsea; King's College; and St George's hospitals all operate milk banks serving the most premature and vulnerable babies in their neonatal units. Elsewhere, St Peter's Hospital in Surrey supplies hospitals within their trust, and the Hearts Milk Bank in Hertfordshire supplies hospitals in England and Wales. To enquire about donating, or access donor breastmilk in the community, contact your local milk bank, or HMB.