She burnt London to the ground and her forces slaughtered everyone who hadn’t fled. So why is Boudica revered as a British hero and feminist icon?

The Romans founded Londinium only a few years before Boudica turned firestarter. And as much as they loved an aqueduct, the toga-botherers also liked a bit of patriarchy. Pater wore the trousers, as it were, and while Roman women could be influential, they could not hold power.

Clearly, Boudica didn’t get the memorandum. Because Boudica had the charisma and cojones to unite tribes, lead armies and shake one of the greatest empires the world had ever known. And shaking was, at that time, very much a man’s game.

Boudica was very much ‘fuck you’ about chauvinist Romans

Didn’t she like straight roads and the introduction of plumbing? Sadly, her opinions on sanitation have been lost to the annals of pisstory, but we know her collision with Roman authority began with the death of her husband, Prasutagus, king of the Iceni.

The Iceni were a tribe of Celtic Britons that lived where modern day Norfolk is, with a bit of Suffolk and Cambridgeshire thrown in. They had an alliance that left them nominally independent, thanks to the king’s pro-Roman vibes. Prasutagus hoped to keep relations sweet by bequeathing his kingdom jointly to his daughters and Emperor Nero. But if female rule was verboten in Rome, it was always going to be maximus impermissus elsewhere. The Treasury was also running out of dollar, so the procurator, Catus Decianus, marched in to the Iceni tribal lands, plundered, ravaged and pillaged, enslaving the king’s family and making free with their goods and chattels. And no one appreciates another man’s hands on their chattels.

Boudica was very much ‘fuck you’ about all this and made her feelings known. Whether they liked it or not, she was Queen, but not yet the Warrior Queen of legend. The Romans responded to her dissent by having her publicly flogged and her daughters raped, believing the only consequence would be their subjugation. For what could a mere woman do when confronted by the might and brutality of Rome? Now imagine a ‘huge mistake gif’, because those abominations led to the deaths of tens of thousands of Romans soldiers and their supporters when Boudica took to her battle chariot.

She gathered the Iceni and a neighbouring tribe, the Trinovantes, whom you might call an Essex firm. The Trinovantes were already raging at having been mugged off at Colchester (Camulodunum); their land and property commandeered to allow a colony of Roman veterans to take over and lord it over them. They united behind Boudica for revenge, rebellion and a right old rumble.

Londinium Calling

While the Governor of Britain, Suetonius Paulinus, was off trying to subdue the Welsh on the island of Anglesey, Boudica’s army marched on an undefended Colchester, destroying Britain’s first city and giving the Romans a taste of their own medicine in the mercy department. A detachment of the Ninth Legion piled in to sort the job out and were subsequently routed in a major victory for the underdog. Catus Decianus, having provoked the rebellion, showed what he was made of by doing a runner from it, to France (Gaul).

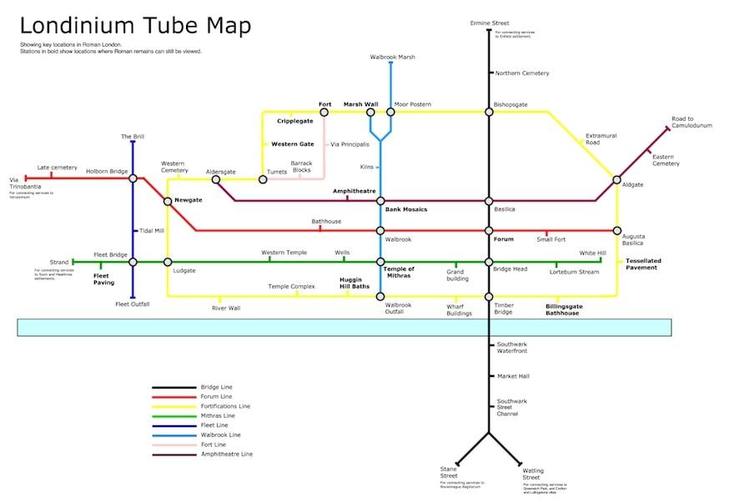

Now there may have been a little partying going on after these glorious, bloodthirsty victories over the invaders. Certainly by the time Boudica approached Londinium, Suetonius had returned from Wales and had evacuated the settlement. Londinium wasn’t really a city at that time, unlike Colchester, but a multicultural centre for trade and business. The lifestyle there was more Mediterranean than elsewhere in Britain. The Iceni probably called it That Londinium, what with all their fancy ways. Most inhabitants fled under the protection of Suetonius. Those that remained were massacred and the buildings of Londinium on both sides of the Thames destroyed. The first London had been razed to the ground.

She caused the Romans some serious shame — not least because she was a woman

Some historians believe Boudica then went on to torch St Albans (Verulamium), but her string of victories could not hold. She made a fatal mistake, being lured into battle against an experienced, professional army, at a location that suited the Roman soldiers. Facing defeat, she is thought to have taken poison to avoid capture. She would never be a slave. The rebellion had ultimately failed, but the name of Boudica would be revered for at least the next 2,000 years. Unlike that of Sue-whatshisname.

There is much conjecture in our understanding of Boudica, as no contemporaneous writings exist. The Roman historian Tacitus, who wrote about these events around 116 AD was clearly writing for a Roman audience when he described Boudica’s revolt. But even he reported the treatment of a native royal family in a way that would have shocked those Roman sensibilities. He may have exaggerated those slain by Boudica’s forces — he reckoned 70,000 — but he didn’t soften the causes of the rebellion.

Dio Cassius’ (155-235AD) account was largely based on Tacitus’, but he upped the death toll for good measure: “Eighty thousand of the Romans and of their allies perished, and the island was lost to Rome. Moreover, all this ruin was brought upon the Romans by a woman, a fact which in itself caused them the greatest shame.”

Her name lives on, unlike Sue-whatshisname

Yes, the revolt was ultimately unsuccessful. But Boudicca’s legend lives on. The Romans had been given more than a bloody nose. They had suffered defeat at the hands of a people they thought of as barbarians and a sex they thought inferior. Their three main centres had been trashed and Suetonius removed for a more lenient governor.

The location of Boudica’s last stand continues to be disputed and her remains have never been found. Norfolk, Gloucestershire, Hampstead and King’s Cross station have all had a claim, though none with compelling evidence. Her statue stands by Westminster Bridge, yet she achieved the destruction of our city that the Luftwaffe could only dream of.

The legacy of the Roman presence in Britain lives on in our food, roads, currency and yes, plumbing. But history is also marked by women who were not cowed by the powerful, who would not be silenced — from Boudica, to Pankhurst, to Thunberg — and we are all the richer for them.