For more of all things London history, sign up for our new (free) newsletter and community: Londonist: Time Machine

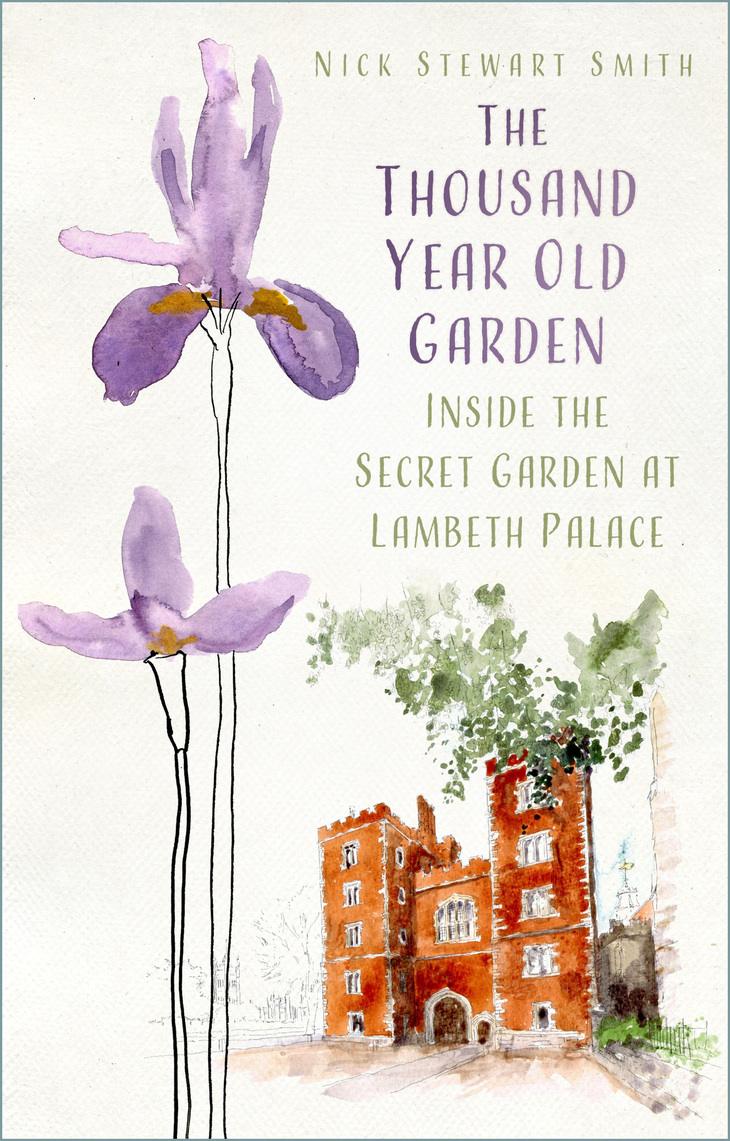

In an extract from his book, The Thousand Year Garden: Inside the Secret Garden at Lambeth Palace, Head Gardener Nick Stewart Smith takes us behind the gates of this ancient urban oasis, to discover its origins.

When I am giving a guided tour, at some point near the beginning I usually mention that the garden was first founded in 1197, the same year as Lambeth Palace itself, according to the official records.

This information is usually met without question and occasionally I have even heard a quiet gasp from the small group around me; maybe some of them are taken aback at the thought of all those centuries of gardening.

In my role as a guide, I realise I might have gone a little too far at times by suggesting that before 1197 there was nothing much to find on the site, implying it was no more than a barren marsh beside an unpromising stretch of the River Thames. Not much was going on, I would intimate, it was just a bleak place of little interest, flat and prone to flooding.

At some point in the 1190s, for various reasons, some of which seem to have been political, the idea came to create something significant here on the sticky marsh alongside the existing wooden church that eventually became St Mary's at Lambeth. The proposal was to build a new palace with a chapel and high stone towers, a wonder beyond imagination rising up from the swamp.

It is hard to say for certain what those first structures might have looked like because few recorded details seem to have survived beyond the deeds describing the purchase of lands for the Archbishop of Canterbury. While so much is unknown, at least there are a few things we can glean concerning the garden from one of the oldest court roles for Lambeth dated 1237, a copy of which can be found in the Lambeth Palace Library archives. The court role records that the palace already had significant orchards, with surplus pears and other fruits being sold to local residents at the main gate. A new herbarium had just been constructed and, in another part of the grounds, hemp and flax were being sown as crops. I saw a beautiful blue flax flower just yesterday, growing wild in the garden. I suppose it could not be some distant relative of those 13th-century flax, although I would like to think that it was.

Another record dated 1322 can be found in the archives, telling of a new wall being constructed around the grounds and the establishment of a rabbit field towards the north end. The rabbits must have been introduced as a food supply, even though meat was not generally approved of in medieval monastic life. A fish or a hen's egg was allowed, now and then, but meat was only to be taken on rare occasions. It is also recorded in the 1322 note that a labouring boy was hired for eight days to dig out 'flowering plants'. I wonder why they were digging out flowering plants back then. It could be they meant something that would be described these days as weeds, a term derived from Anglo-Saxon and in use back then, although, to many, it would often have meant either grass or a herb. A plant growing in the wrong place is often defined as a weed, posing a question any gardener anywhere in the world has to consider — which plants are allowed into the garden and which are not?

Maybe the hired garden boy mentioned in the note of 700 years ago was pulling out things like leopard's bane, sow thistle or cat's ear, just as some of the garden team were doing here in the same space only last week. Those weeds mentioned are tenacious plants that endure through many years and that is why they are such good survivors. You can never quite get rid of them, not even if you really want to.

But where did he come from, that gardening boy of 1322? Where did he live? The area around the medieval Lambeth Palace was fairly sparsely populated, most of the local dwellings being humble structures somewhere along the riverbank, although there were some well-established towns or villages nearby. There was Camberwell and Chenintune, which became known as Kennington, also Brixieton, now Brixton. As dawn was breaking, he must have trudged along the cold, muddy tracks to work at this strange place with stone towers and vast gardens, all built on the dank marshlands.

Trying to fit in with the peculiar ways of the garden team, set to work pulling up plants or digging them out from the herb garden or the many raised beds where vegetables were growing, he must have had to learn very quickly which of those plants were wanted and which were not. When he looked up, all around the garden area he would have seen the newly built high wall made of stone, topped with a neat finish of fresh thatching. But there would be no time to linger for the boy to admire his surroundings, he had to get back to work and, with luck, those few days of labour might lead to full-time employment for him if things went well.

From the archived record we know that he was paid a penny for each of the eight days he was said to have been there. It might not sound much, but those were hard years to live through. From 1314 to 1316, wild storms and almost perpetual rain had devastated food supplies in England and much of Europe, the terrible weather causing what became known as the Great Famine. Prices were very high and essentials such as bread were difficult to find. They were years of suffering and there are many stories of parents abandoning their children when they could no longer care for them. Perhaps the gardening boy was a child in that situation trying to fend for himself alone? Whatever the case, the eight pennies he earned for his labour would probably have been of great help, at least for a while.

The Thousand Year Old Garden by Nick Stewart Smith, published by The History Press