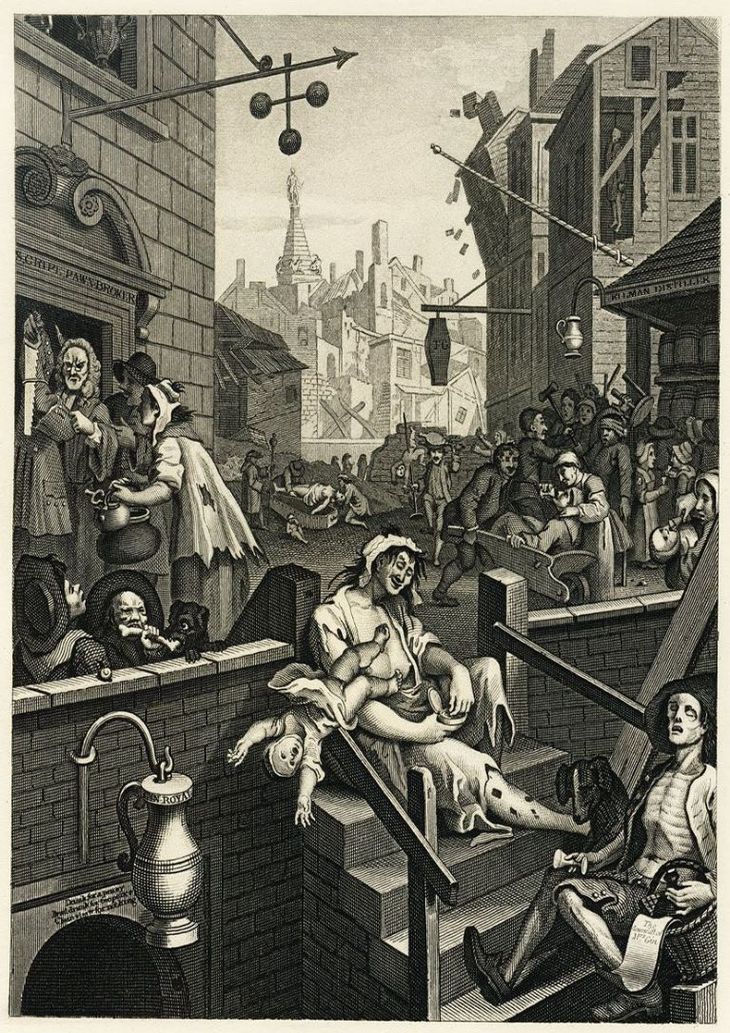

We may have seen a gin renaissance over the last few years but London has had a long, and not entirely healthy, love affair with mother's ruin.

Using material from Revolution, the fourth volume of his History of England, historian Peter Ackroyd discusses the disastrous consequences of 18th-century London's craze for gin.

1. Gin was Dutch and therefore preferable to suspicious French liquors

The craze for gin began, approximately, in 1720 but it had been readily available since the time of the Glorious Revolution in 1688. William III brought the drink with him from the purlieux of Rotterdam, and soon enough the Dutch spirit had supplanted the taste for French brandies. Anything French was suspect. The soldiers of William's army were encouraged to imbibe 'Dutch courage' before action.

2. You could buy gin literally anywhere

The gin was sold in the shops of weavers, dyers, barbers, carpenters and shoemakers; the workhouses, prisons and madhouses were awash. There were degrees of nastiness and discomfort. Inns had lodging rooms for guests, while alehouses provided 'houses of call' for the various trades of the city; the brandy shops or dram shops were of the lowest grade, where cellars, back rooms and holes in the wall provided shelter for copious consumption.

Gin was sold from wheelbarrows, from temporary stalls, from alleys, from back rooms and from cheap lodging houses. It was consumed greedily by beggars and vagrants, by the inmates of prisons or workhouses, by Londoners young and old.

3. Even children got a taste for gin

It was a particular favourite of women, who also used liberal quantities of the stuff to silence children.

The consequences were dire. Children would congregate in a gin shop, and would drink until they could not move. Men and women died in the gutters after too much consumption. Some drinkers dropped dead on the spot. It was not at all unusual to see people staggering blindly at any time of night and day. Fights, and fires started out of neglect, were common. A foreign observer, César de Saussure, noted that "the taverns are almost always filled with men and women, and even sometimes children, who drink with so much enjoyment that they find it difficult to walk on going away".

4. 18th century London had more gin shops than we have fast food restaurants

William Maitland, whose The History of London was published in the mid-18th century, reckoned that 8,659 gin shops were operating in the city, with particular clusters around Southwark and Whitechapel. The sale of spirits had doubled in a decade, with 5.5 million gallons purchased in 1735.

5. The government tried to intervene, without much success

Several attempts were made to administer or temper the sale of gin, with diverse consequences. The Gin Act introduced a duty of 20 shillings per gallon on spirituous liquors, and retailers of gin were required to purchase an annual licence of £50. This simply served to encourage the illicit selling of spirits that now expanded out of all proportion. Gin was sold as medicinal draughts or under assumed names such as Sangree, Tow Row, the Makeshift or King Theodore of Corsica.

6. In the face of prohibition, London's gin traders got creative

Subtle means of distribution were invented. An enterprising trader in Blue Anchor Alley bought the sign of a cat with an open mouth; he nailed it by his window and then put a small lead pipe under one of its paws. The other end of the pipe held a funnel through which the gin could be poured. It was soon bruited 'that gin would be sold by the cat at my window the next day'. He waited for his first customer, and soon enough he heard 'a comfortable voice say, "Puss, give me twopennyworth of gin"'. The coins were inserted into the mouth of the cat, and the tradesman poured the required amount into the funnel of the pipe. Crowds soon gathered to see ‘the enchanted cat’ and the liquor itself came to be known as 'Puss'.

7. Londoners rioted in the streets over the lack of gin

The evidence of Westminster interference in the once flourishing gin trade provoked riots in the poorer parts of the city; the turmoil became so violent that it was deemed by some to be a danger to the state. Shoreditch and Spitalfields were practically under siege.

Informers, those who swore to the justice that a certain establishment was selling gin unlawfully, were hounded and struck down by the mobs. Some of them were beaten to death, while others were ducked in the Thames, the ponds, or the common sewers. It was a form of street power. A woman in the Strand called out "Informers!" whereupon 'the Mob secur'd' the man involved 'and us'd him so ill that he is since dead of his Bruises'.

The legislation of 1736 proved impossible to enforce. The Act was modified in the light of public complaint and a new act was drawn up seven years later; it was known as 'the Tippling Act', and in 1747 the gin distillers won back the right to sell their product retail. Spirit, raw or mixed with cordial, was once more the drink of choice.

8. Eventually everyone just started drinking tea instead

In one of those ultimately unfathomable changes of taste, the craze for gin subsided. This had nothing to do with the attempt at prohibition, which had become a dead failure. Bad harvests rendered gin more expensive. The influence of Methodism was growing even among the urban poor. And, suddenly, there was the new fashion for tea.

Revolution is the fourth instalment in Peter Ackroyd’s History of England. Read an extract here.