It does not yet smell of roses. But from boiled pee to hi-tech sludge digesters we look at the history of how London has assuaged its sewage problem. It’s a story involving Bibles, bugs and peppermint.

Recycling

Pee was profitable. Buckets of the stuff could be collected for tanneries, to make saltpetre, or even boiled down as a source of phosphorus.

Solid ‘night soil’ was nasty, but at least the farmers could get some use out of it. So it was carted beyond the city walls. ‘Sewage farm’ is one of those archaic terms we still use, from when the capital’s excrement was flung on the fields to seep away and simultaneously fertilise the fruit and veg.

Removal

Recycling of sewage came to a rapid end when the water closet caught on after the Great Exhibition of 1851. The WC is a luxury compared to a bucket or hole in the ground, but it dilutes the waste, making it too cumbersome to cart away. It trickled from pipes into ditches and ultimately into rivers, culminating in the Great Stink of 1858.

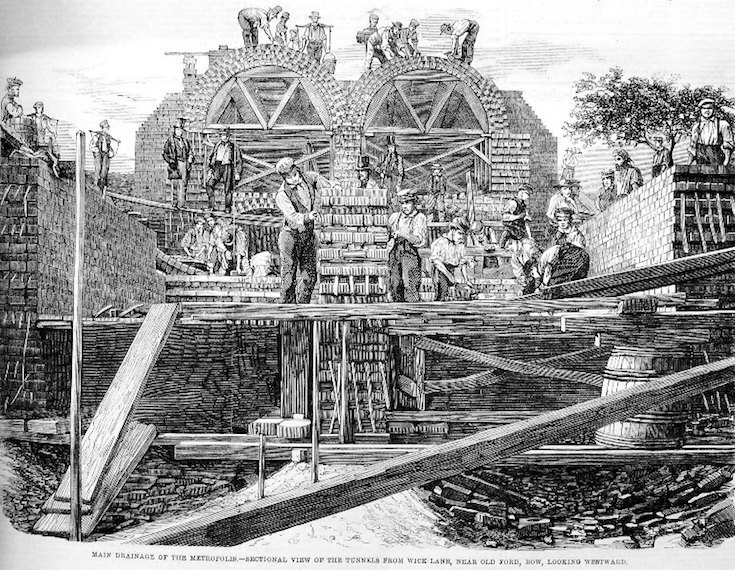

It is an often told story that Sir Joseph Bazalgette took the crap out of London with his sewers. The core of our current system with its generous dimensions and celebrated workmanship was completed by 1870. But it tends to be forgotten that he still poured the sewage untreated into the Thames in Essex and Kent — where no one important would notice.

Others clung to the idea of piping the poo to the farmers. Elisha Oldham advocated such a system in the 1860s. He claimed the force of compressed air could expel the waste Essex-wards at perhaps 600 miles per hour. We don’t know what Essex had ever done to him.

Precipitation

No.1s and No.2s have always presented different challenges and mixing them up in the WC only postponed the difficulties. The liquid dissipated out at sea but mud banks of merde began to form in the Thames estuary.

Numerous schemes were developed for trying to divide and conquer sewage by precipitating solids out of the liquid. The benefit was that it allowed some of the sewage to fertilise farms again. Brands appeared such as ‘Tottenham Sewage Guano’. One inventor in the 1860s found a Biblical recipe to make his sewage precipitate. There was even an attempt by a designer of public buildings to turn the solidified stools into building cement. ‘Modern architecture? It’s just a pile of shit!’

Sewage is still separated into liquid and sludge (mostly the roughage which we wisely consume). The liquid passes into the river, and from 1887 until 1998 a fleet of ships dumped London’s solid sludge further offshore.

Science Lags Behind

Cholera began to haunt London from 1832. Dr John Snow, who removed the pump handle during the 1854 Soho outbreak, is a hero of our age rather than his. He was hardly noticed. Pasteur exposed the role of microbes in fermentation and putrefaction in 1860s in Paris. Around the same time our own Edward Frankland (1825–1899) began to suspect a link between sewage and cholera. But he was just a chemist. Cholera was the domain of doctors. They saw themselves as curing diseases (though they generally failed) not preventing them. Frankland too was ignored, but kept his interest in clean water as we shall see. German physician Robert Koch finally found a cholera bacillus in 1883.

Filtration

In the 1870s Frankland investigated filtering sewage through gravel, a variation on the old sewage farm idea, and found it efficacious. In many places the idea of farm as filter persisted.

"Great diversity of opinion existed as to the best vegetation for a sewage farm… In Sutton, in recent years, peppermint has been found profitable." (1899)

Deodorisation

'Bad air' was long thought to be the root cause of disease. Sewage started to be deodorised with various additives. When the Royal Commission on Metropolitan Sewage Discharge found fault in 1884 it fell to William Dibdin (1850-1925) to deodorise the sewage flowing into the Thames. He treated the effluvia at Crossness and Beckton with common chemicals.

Dibdin was confident of his mastery over manure. A few years before, Dibdin had won a remarkable wager. On a steamer off Beckton he drank a glass of Thames water filled from the river without ill effect.

Digestion

As Dibdin continued to improve his filters in the 1880s the realisation gradually dawned that the gravel was not acting as a filter but as a home for microbes to colonise. These broke down the feculent burden of the liquid and the water that emerged was cleansed. Such bacteria need oxygen. A familiar sight at a sewage works is liquid trickling over stone. This helps it to take up oxygen. Alternatively air is bubbled through.

Hydrolysis

Around 1800 Humphry Davy and Joseph Priestley discovered that decaying vegetation produced methane gas. It was not until the 20th century that the process was applied to break down intractable fibrous sewage into something soluble, a reaction called hydrolysis. This set of beneficial bugs work best without oxygen. The methane by-product of the sludge digester can burn to generate electricity. Today, sludge at Beckton and Crossness is hydrolysed by ever more sophisticated processes and the residue turned into (sterile) fertiliser once again. Rose food, anyone?