There are so many places in Londons of centuries gone by we'd love to experience. Dr Matthew Green, author of London: A Travel Guide Through Time, takes us to three of them.

The Frozen Thames, Georgian London (c. 1716)

It’s a travesty of history that the Thames no longer freezes over. If only the Victorians hadn’t narrowed the river quickening its flow by building embankments. But travel to December 1715 and you’ll find it frozen solid from London Bridge to Charing Cross.

Don’t expect it to look like a smooth ice-rink. Expect “a rude and terrible appearance”; “as if there had been a violent storm and it had froze the waves just as they were beating against one another”.

On the ice you'll find a riotous, carnivalesque atmosphere, with Londoners relishing the surreal sense of unexpected liberty brought to them by ‘Freezeland Fair’, as they walk from bank to bank.

You’ll have to pay the temporarily-redundant watermen a small fee to set foot on — and leave — the ice, and they may also dig channels, lay planks, and demand further tolls.

You’ll see tents propped up with oars containing coffeehouses, Houses of Geneva (gin booths), poetry jams, and elsewhere, games of nine-pin bowling, and animals being baited on the ice in a ring of spectators. If you see a printing press, get them to churn out a little bespoke memento — plays on the transience of ice versus the permanence of print, these are very popular (Hogarth had one made for his pug dog Trump in 1740).

Whatever you do don’t stray from the rutted paths, or you may never be seen again — and spare a thought for the poor people frozen to death in their beds.

If you see any cracks in the ice — get off, quick. Frost fairs thaw dangerously quickly; before you know it, islands of ice will be floating downriver taking booths and printing presses and terrified people with them, pummelling any vessels lying in the way, and smashing into the arches of London Bridge.

London’s final frost fair came in 1814. Reportedly “a very fine elephant was led across the Thames a little below Blackfriars Bridge”.

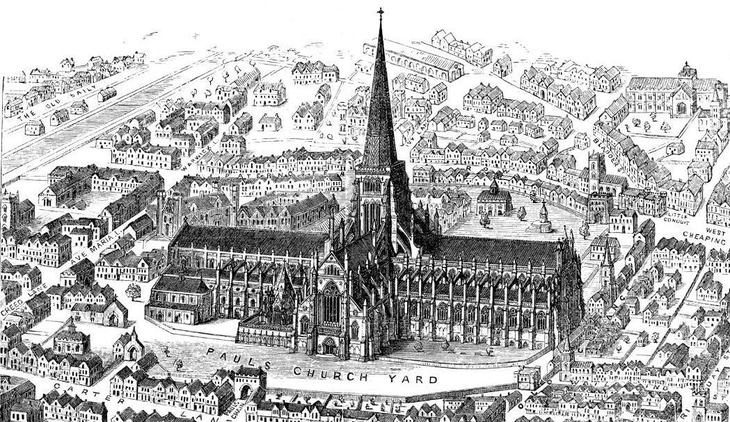

Medieval St Paul's (c. 1280)

It will be the spire you notice first — monumental, of lead-and-timber and rising to 489ft. Not until 1964 will another building rise so high in London.

Very much unlike Wren’s domed successor, the cathedral in front of you is stern and remorseless in its Gothic vernacular, all flying buttresses, sharp turrets and rounded, Norman-style windows.

Go in. Plumes of incense fill the air. Pillars shoot to the ceiling vaults, connected by arches forming a towering colonnade. Peer into the dim chantry chapels behind the colonnade and you’ll see priests slicing their hands through the air singing prayers for the dead and, in one place, a fragment of Thomas à Becket’s skull in a gleaming reliquary — or, in the words of Chaucer’s Pardoner, pigs’ bones.

If you’re expecting a holy atmosphere, forget it. This is the biggest covered space in London, full of lawyers, ale-wives, quack doctors and tradesmen tossing coins in the baptismal font.

Boys kick a pig’s bladder filled with peas and fire arrows at the jackdaws in the rafters, sometimes smashing the holy windows. It is also London’s main news corridor and a promenade of fashion — look out for knights in long, floppy shoes with a falcon or hawk perched on their wrist.

The hubbub is fitting testament to how ingrained the church is into everyday life. Riding high in the eastern wall is the Rose Window bathing an extraordinary, pyramid-shaped shrine in bright shafts of kaleidoscopic light. This belongs to Erkenwald, the patron saint of London, largely forgotten in the 21st century. One of the city’s first bishops, he liked, after his canonisation, to perform vengeance miracles on practically anyone who disrespected him, gouging out eyes, spilling brains, and beating people up in their dreams with his pastoral staff.

The spire of Gothic St Paul’s was destroyed in a lightning strike in 1561 and the rest of it in the Fire; Erkenwald didn’t survive the Reformation but there is, to this day, an Erkenwald Street in East Acton though how the fiery saint landed in this sleepy pocket of suburbia is a mystery.

The Globe, Jacobean Bankside (c. 1610)

You’ll recognise its external appearance from the 21st century though it’s in a slightly different place, its plaster less starched-white and the whole structure rickety.

Plays begin at 2pm. Join the long queue and drop a penny into the small earthenware box with a lustrous green glaze; when full, it will be smashed open in the box office behind as coins pour into the coffers.

Go into the pit and stand amongst the “stinkards”, fully exposed to the elements. You may be annoyed to see young blades arrive late, mount the stage with their stools, and sit smoking as the action rages around them.

The stage lies in shade unless the players come to the front where their faces are brilliantly illuminated. Don’t just watch in silence as audiences boringly do in the 21st century; you are part of the theatre yourself. It is your prerogative to hurl pippins, pipes, bottled ale, even stones at the stage, and feel free to join in the stinkards’ chorus of demands to see a different play altogether if it’s not to their liking.

You will love the special effects. Men hide in the wings and yell “fight! fight! fight!” during battle scenes, pigs’ bladders brimming with blood are routinely splashed on stage, and when ghosts appear, fireworks are launched through the trapdoor. Listen in particular for the thunder effect, achieved by hirelings rolling cannonballs around the gallery roof or letting off fireworks behind sheets of metal.

In time, a playwright called John Dennis will invent an ingenious new method of replicating thunder, only to see it nicked by a rival playhouse for a performance of Macbeth. “How these rascals use me!” he shouted, “They will not let my play run, but they steal my thunder!” Few idioms can have been forged in such fury.

The original Globe burned down in 1613 when a cannonball fired during a performance of Henry VIII set the thatched roof on fire; its prudently-tiled successor was destroyed by the Puritans in the 1640s.

See also: Three hellish places from London's past we wouldn't want to visit.