You may correctly be able to say that Tower 42 was built after the Tower of London. But can you give a construction date for any buildings in between — just by looking?

Much of central London is Georgian. But can you tell late from early Georgian? And can you tell late Georgian from early Victorian? Can you read the window code? And what the hell is baroque?

Let us show you how to identify what period any building you're looking at is from, so you can impress your friends with your knowledge.

Medieval

Churches and fortifications were once about the only buildings in London other than hovels. Towers and spires dwarfed the homes round about, and the skill of the stonemasons continues to dazzle us.

There are very few examples of medieval buildings still standing in London today.

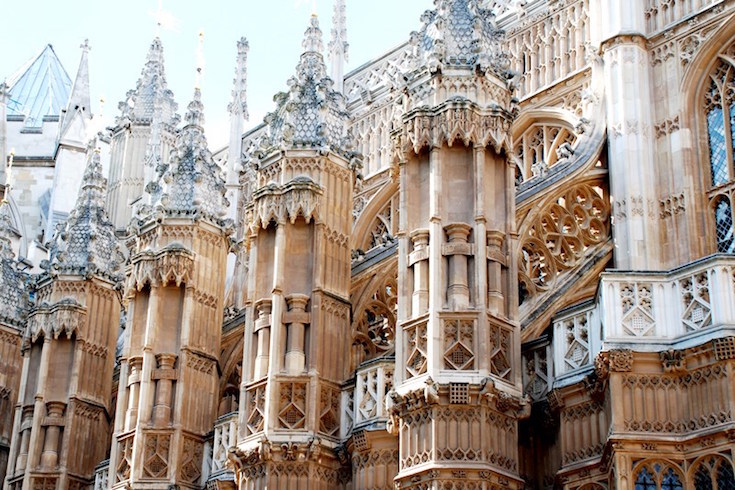

One of the most spectacular is Westminster Abbey — with its pointy bits, fan vaults, rose window, flying buttresses and gargoyles — looks typically 'gothic'. But it was not built by Goths. Somebody way back joked that it was, and the term stuck. It's actually medieval.

One key feature to look out for on such buildings is the flying buttresses — not put there for decoration but to counter the tendency of the roof to push the walls out sideways; experience hard won because those old cathedrals did collapse sometimes.

Ships brought the heavy stone around the coast from Portland. London is full of greyish white Portland stone, a kind of limestone, used over several centuries (so it doesn't really help us date buildings), which dazzles us in the sun and echoes the grey clouds when the days are dismal. The Abbey is the concoction of centuries of architects since medieval times. Confusingly some of the later ones harked back to the beginning.

Other examples of medieval architecture in London (apart from parts of the Tower of London) are a smaller church in the Temple, and the Jewel Tower opposite Parliament, which is a fortified strong point from 1366. St Helen's in the Square Mile and St Bartholomew the Great in Smithfield are two others worth seeking out.

As none of these really have any one architectural idiosyncrasy in common, it's probably just easier to memorise them as medieval by heart.

Tudor (1485-1603)

In Tudor times the hovel grew up. An original(ish) Tudor building is Staples Inn, High Holborn. Its structure of white panels made from ‘wattle’ (sticks) and 'daub' (mud and manure) between dark timber beams made ideal fuel for fires — one reason why so little survives in London. It is not to be confused with suburban mock Tudor which was put up by garden gnomes in the 20th century.

Stone was infrequently used in London because it was difficult to cut and carry, but there was clay around London to make bricks. These were still expensive because they were handmade — and they look it.

Tudor royalty lived in palaces made of brick (Hampton Court and St James’s Palace, for example). They have windows, but glass was also expensive so the windows are small. Although not without decoration (Hampton Court has its beasts, its patterned chimneys and its astronomical clock) the Tudor palaces were relatively plain and functional compared with what came next. A small Tudor survivor is Sutton House in Hackney.

By this time, there was no point in building castles. Gunpowder could demolish them.

Stuart (1603-1714)

Sir Christopher Wren wanted to use gunpowder to demolish the charred ruins of St Paul's after the Great Fire of 1666 but the idea upset the neighbours. His new cathedral was put up (mostly) in this period and was built with Portland stone, as was his Greenwich Royal Hospital. These were part of a mushrooming of buildings in Portland stone which started with Inigo Jones's Whitehall Banqueting House of 1622.

In the same way that Mediterranean holidays popularised calamari fritti in English pubs, the wealthy Stuarts were inclined to travel to Europe (or went like Charles II, as refugees) and when they returned their tastes were coloured by what they had seen.

Words such as 'baroque' enter retrospective descriptions of these buildings. The word (a joke again) means 'exuberant style… degenerating into tasteless extravagance' and would not have been applied by the architect to his own work. World trade was blossoming. There was money around so everything came with knobs on, and probably scrolls and seashells too, even beyond Gothic levels of embellishment. There was restraint under Cromwell's Puritan rule, but not for long.

Another Stuart building, on the outskirts of London, is Ham House, built of red brick and incorporating sash windows. Perhaps Londoner Robert Hooke, experimenter for the Royal Society, invented the counterbalanced sash window. But then Hooke claimed he thought of everything first. Sash windows suggest to us that a building came after 1670.

In 1696 Window Tax was introduced to raise funds for the new coinage introduced by Sir Isaac Newton at the Mint. That caused owners of large houses to brick up some of their orifices. These can still be seen. It was tax avoidance. Any evasion was easy to spot. But just to confuse us, sometimes architects designed ‘blind’ windows which never had any glass. Lack of symmetry or contrasting brickwork may point to bricked up windows.

Health and safety (1709)

Lessons will be learned, we often hear, but it takes time. In 1709, 43 years after the Great Fire of London, a law was introduced to protect homes by recessing their wooden window frames by 4in. When they caught fire the sparks from recessed frames could less readily float up and ignite the roof.