Victorian London: it's nothing like the London of today. Or is it? We leaf through five seminal non-fiction Victorian works, comparing their visions of London to those from the modern day city. While some pictures of the city have changed beyond all recognition, there are also one or two surprising similarities.

Charles Booth's poverty maps (1889-91)

One of the great philanthropists of the Victorian age, Charles Booth spent years trudging the streets of London, meticulously detailing the quality of life in each pocket of the city. Here's how Booth classified the areas of his maps he highlighted in black:

The lowest class which consists of some occasional labourers, street sellers, loafers, criminals and semi-criminals. Their life is the life of savages, with vicissitudes of extreme hardship and their only luxury is drink.

And here is that exact area of Nine Elms Booth was talking about:

Of late, the area has become, let's say, slightly more salubrious. Here's some promo spiel from the Battersea Power Station website — almost the exact same area which Booth had deemed 'savage':

Battersea Power Station will become one of the most attractive places to live, work and visit. One of London's most popular villages, this is a location that global brands such as Vivienne Westwood, Victoria Beckham, Gordon Ramsay and Foster + Partners, (architects of Battersea Roof Gardens) already call home. From its vantage point on the River Thames, and next to Battersea Park, Battersea Power Station occupies one of the most accessible and desirable locations in London.

Though we're not sure about being neighbours with Gordon Ramsay, there's no doubt that this quarter of Battersea is a much more pleasant place to live now than in Booth's day. In fact, many of us would struggle to afford it. A few decades earlier than Booth, Punch co-founder Henry Mayhew had carried out his own research into the lives of Londoners. Let's take a Victorian snapshot from him.

London Labour and the London Poor (1840-51)

Perhaps the most famous book exploring Victorian London's poverty was Mayhew's London Labour and the London Poor (1840-51). Here's a passage in which Mayhew explores Rosemary Lane, on the fringes of the City:

As you walk down "the lane," and peep through the narrow openings between the houses, the place seems like a huge peep-show, with dark holes of gateways to look through, while the court within appears bright with the daylight; and down it are seen rough-headed urchins running with their feet bare through the puddles, and bonnetless girls, huddled in shawls, lolling against the door-posts. Sometimes you see a long narrow alley, with the houses so close together that opposite neighbours are talking from their windows; while the ropes, stretched zig-zag from wall to wall, afford just room enough to dry a blanket or a couple of shirts, that swell out dropsically in the wind.

It's a poetic account, but one that can't stifle the squalidness of the whole place. Rosemary Lane has since been renamed Royal Mint Street (incidentally both would go well with lamb), and is now home to luxury developments like this one:

Introducing Royal Mint Gardens, one of London's most prestigious and exiting new residential developments. An address of enormous prestige and heritage, combined with visionary architecture, contemporary design, superb amenities and spectacular views.

Enjoy the perfect London river lifestyle with St Katherine Docks just minutes away from Royal Mint Gardens. This vibrant marina with its luxury yachts, waterside restaurants, shops and cafes, sits in the historic heart of London...

As with the Booth extract, the London of today is safer and cleaner than its Victorian counterpart. But we can't help feeling it sounds somewhat more devoid of life too. This becomes more acute when we tear out a paragraph from our next book, London: A Pilgrimage.

London: A Pilgrimage (1872)

In the Gustave Doré and Blanchard Jerrold's London: A Pilgrimage (the former was the illustrator, the latter his scribe), the area around St Katherine Docks is recalled with colour and bustle:

We were sitting upon some barrels, not far within the St Katherine's Dock Gates, on a sultry summer's day, watching the scene of extraordinary activity in the great entrepot before us. "There is no end to it! London Docks, St Katherine's Docks, Commercial Docks on the other side, India Docks, Victoria Docks; black with coal, blue with indigo, brown with hides, white with flour; stained with purple wine, or brown with tobacco!" The perspective of the great entrepot or warehouse before us is broken and lost in the whirl and movement. Bales, baskets, sacks, hogsheads, and wagons stretch as far as the eye can reach... The solid carters and porters; the dapper clerks, carrying pen and book; the Customs' men moving slowly; the slouching sailors in gaudy holiday clothes; the skipper in shiny black that fits him uneasily, convoying parties of wondering ladies; negroes, Lascars, Portuguese, Frenchmen; grimy firemen... all this makes a striking scene that holds fast the imagination of the observer...

Here's Doré's illustration of such a scene at St Katherine Docks:

Compared to all that, the docklands of 2015 sound rather dull, bleak even. Here's a description of St Katharine Docks from its official website:

Central London's only marina, the docks are now home to a collection of high quality offices, restaurants, bars, shops and homes. Just a stone's throw from Tower Bridge, this vibrant community is one of the capital's hidden gems and an unrivalled location for working, living and relaxing.

Yawn. In fairness, across the Thames at Pickle-Herring (now Shad Thames) Doré and Jerrold also talk about "hard-visaged men, breathlessly competing for 'dear life' [who] glance, mostly with an eye of wondering pity...", and we known the docks weren't exactly a waterside picnic. But though London's docks are slowly being regenerated (and some of them are even clean enough to swim in now), the atmosphere rarely compares to the scenes generally depicted in London: A Pilgrimage.

People of the Abyss (1902)

At the turn of the century, Jack London was a tourist who posed as an East Ender in order to write about the lives of working class people (as far as we know he didn't adopt a Dick Van Dyke accent). His 1902* book The People of the Abyss begins ominously:

"What I wish to do is to go down into the East End and see things for myself. I wish to know how those people are living there, and why they are living there, and what they are living for. In short, I am going to live there myself."

"You don't want to LIVE down there!" everybody said, with disapprobation writ large upon their faces. "Why, it is said there are places where a man's life isn't worth tu'pence."

Later, London goes to visit a workhouse in Whitechapel, where he finds:

... a most woeful picture, men and women waiting in the cold grey end of the day for a pauper's shelter from the night, and I confess it almost unnerved me. Like the boy before the dentist's door, I suddenly discovered a multitude of reasons for being elsewhere. Some hints of the struggle going on within must have shown in my face, for one of my companions said, "Don't funk; you can do it..."

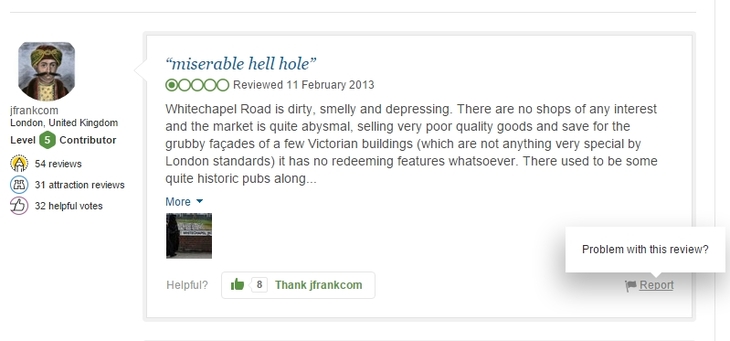

Now, of course Whitechapel is a diverse, coveted part of town which has the likes of Genesis Cinemas, Tayyabs and One Mile End microbrewery. The thing is, a quick visit to Trip Advisor suggests that many tourists are far more unimpressed and unnerved with the area than Jack London ever was:

Whether or not you agree with this review (obviously we don't) it isn't one of a kind. In fact Whitechapel Road is listed as #960 of 1,273 things to do in London. What does all this prove? London will always be good tourists and bad tourists.

*We know that technically the Victorian age ended in 1901, but 1902 is close enough, and anyway, many of London's adventures would have taken place before then.

Sketches by Boz, 1836

And if that doesn't convince you, here's something that shows some things really do never change. One of Charles Dickens's earlier books — Sketches by Boz — recounts his encounters with London folk. In this passage, Dickens records the arrest of a pickpocket in Covent Garden:

About a twelvemonth ago, as we were strolling through Covent-garden (we had been thinking about these things over-night), we were attracted by the very prepossessing appearance of a pickpocket, who having declined to take the trouble of walking to the Police-office, on the ground that he hadn’t the slightest wish to go there at all, was being conveyed thither in a wheelbarrow, to the huge delight of a crowd.

If you're still having trouble picturing the scene, here it is:

Almost two centuries later, Covent Garden's pickpockets remain at large, as this excerpt from an Evening Standard article from 2014 reports:

A police notice deterring pickpockets has been put up in Covent Garden — written in Romanian. The bright yellow sign, outside Covent Garden Underground station, states: ‘Ofiteri de politie in civil opereaza in aceasta zona.

In a twist of irony, the Standard article references a book that Dickens, back in his Boz days, Dickens was yet to have formed in his head:

Jack Gordon, chairman of Hyde Park Safer Neighbourhood Ward Panel, told the Mail on Sunday: “People around here are fed up with the pickpocketing — the place has turned into Fagin’s kitchen."

It is a shame we don't parade pickpockets around in wheelbarrows nowadays though.