Visit a royal Georgian chocolate room, then take a tasty tour of central London chocolate houses.

Admiring the award-winning handiwork of London’s best chocolatiers, currently at the top of their game, we assume we’ve never had it so good – but we are wrong. In fact, in the 17th and 18th centuries, chocolate – or more precisely hot chocolate (the drink preceded solid chocolate) – was an expensive luxury prepared with exotic flavourings and fragrant spices. Cocoa beans had just been introduced to Britain, so it became fashionable among the rich and the royal to have separate chocolate kitchens in their homes, with speciality chocolate-making equipment and personal chocolate chefs. This decadence continued outside, in the hedonistic chocolate houses that had started springing up around London.

A Chocolate kitchen discovered

One such royal chocolate kitchen has been discovered at Hampton Court Palace. It recently opened to the public, to coincide with the 300th anniversary of the start of the Georgian era. It’s housed within the magnificent Fountain Court, where several other kitchens and larders of the period are located, including a Confectionery and a Spicery. Meat and fish weren’t cooked in this area because of their strong smell; the rooms were used only for preparing elegant private dinners.

The Chocolate Kitchen, the only original surviving one in the country, comprises three rooms: two compact kitchens next to each other where hot chocolate was prepared from scratch, plus a small Chocolate Room nearby for storing equipment and tableware. On our visit, curator Polly Putnam and food historian Marc Meltonville explained how all three were used as cramped, dusty storage spaces for many years, before being ‘discovered’ via research documents.

With the aid of clever, state-of-the-art wall projections, the first room demonstrates the initial process of roasting and milling the cacao beans. Yes, making hot chocolate began by preparing the beans first: there were no short-cuts, and certainly no cocoa powder used. There’s a smoke rack, bean roaster and fireplace for the roasting; plus shelves for storing pots, pans, spoons, ladles, and jars of spices.

In the adjacent second room, Thomas Tosier, the renowned personal chocolate chef to George I and George II, would transform the roasted beans into hot chocolate. Here a costumed actor playing Tosier demonstrates how the beans were crushed on a Mexican metate grinding stone until liquefied. There’s an attractive display of cocoa nibs and aromatic spices like chillies, cardamom, allspice, cumin, aniseed and vanilla used for flavouring the drinks. The crushed beans were turned into hot chocolate using a special stirring whisk called molinet. The drink was then served in a ‘chocolate pot’ that looks very much like a long, narrow teapot.

Nearby there’s a slightly bigger Chocolate Room that was once used for storing valuable serving equipment, including silverware, glassware and table linen. This is where Tosier put finishing touches to the royal drink. Whereas once it would have been served in silver or gold chocolate pots and poured into porcelain cups, here you’ll find replicas of the original.

In addition to chocolate pots, there are pestle and mortar, syllabub glasses, and chocolate cups with bulbous bases. Most notable are the extremely rare ‘chocolate frames’ – beautiful, ornate metal cup holders for placing dainty little chocolate cups. This room is a homage to British craftsmanship: highly skilled goldsmiths and glass makers were especially commissioned to recreate the original 18th century designs, based on ones found in old inventories and archaeological pieces.

There’s also a mantelpiece here, over which hangs a striking portrait of Tosier’s glamorous wife, Grace. Something of a celebrity in her time, she was known for her flamboyant hats and mittens, and decorating her cleavage with flowers. She was a successful businesswoman, who fronted her husband’s chocolate house in Greenwich. To create a nightclub feel where royalty flocked for celebratory occasions, she even had a dance floor built in.

Chocolate tours

These chocolate houses were notoriously debauched places with smoky, candle-lit interiors, where the uber-rich socialised amid the intoxicating smells of sweat, perfume and bubbling cauldrons of chocolate. While the one run by Mrs Tosier might now be lost in the mists of time, Unreal City Audio’s Chocolate House Tour brings some of the former ones around St James’s alive.

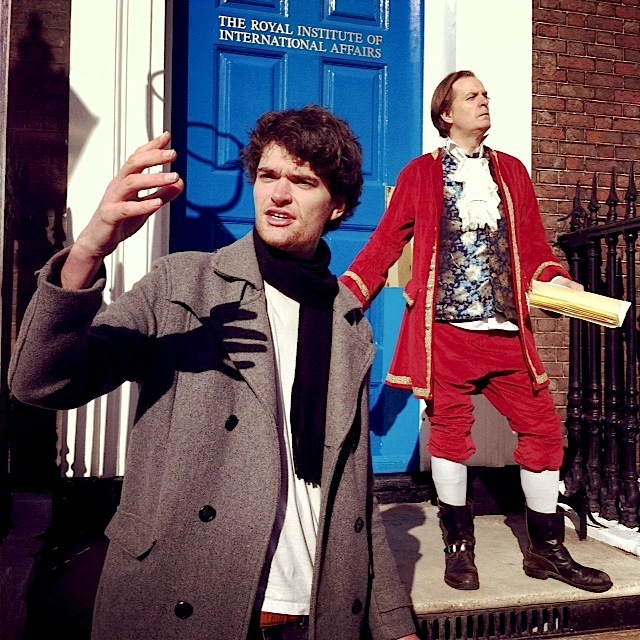

Unrelated to the Chocolate Kitchen, yet giving a fascinating insight into the consumption of chocolate at around the same time, this two-hour walking tour is a new initiative led by historian Dr Matthew Green. Covering the area around Jermyn Street, St James’s Square, Pall Mall, London’s smallest public square Pickering Place, and St James’s Street via several back streets and alleyways, its aim is to show how the drink corrupted London’s most fashionable district.

First, we’re given the historical context of the chocolate houses, with costumed actors providing much merriment along the way. We meet Cosimo III de Medici (1642-1723), the Grand Duke of Tuscany, a chocoholic tyrant who frequented St James’s Square and introduced luxurious hot chocolate to Europe; and the Spanish Conquistador Hernan Cortes.

Unlike the original Aztec hot chocolate flavoured with chillies and the ‘blood of sacrificial slaves’, Medici’s famous version was headily perfumed with jasmine, cinnamon, vanilla beans, musk, ambergris and citrus peel. But something dark lurked under its glossy and aromatic surface: chocolate came to be associated with murder, with poison-laced drinks being used for murdering enemies and wives.

Further along, we discover that the first chocolate house was opened by a Frenchman in Bishopsgate; but it was here in St James’s that they truly flourished. At Pall Mall, we learn that the Royal Automobile Club was, in 1692, the Cocoa Tree chocolate house, where Jacobites gathered to gossip, cook up conspiracies, plot downfalls, gamble with local aristocrats, and mingle with highwaymen disguised as dandies. Who knew?

Walking down the narrow Crown Passage, a picture of slums, alehouses and brothels vividly conjured up in our minds, we’re horrified (and guiltily amused) to hear about someone dying at Ozinda’s chocolate house by falling into a simmering chocolate cauldron. And at the Economist Plaza in St James’s Street, we learn about White’s, the most notorious chocolate house of them all. It was so seedy, and such a hothouse of dubious betting and gambling, that the fire that eventually burnt it down was considered a divine intervention. Eventually the many chocolate houses of the area became sedate gentlemen’s clubs, which they remain to this day.

Of course, it’s not all one historical fact after another without a taste of the sweet stuff. During the Chocolate House Tour, you’ll sample a shot of the excellent Cocoa Hernando’s thick, rich, spicy baroque hot chocolate, similar to the original. And at Hampton Court, a ‘flight’ of four delicious chocolate drinks is available to purchase at £3.95 at the Fountain Court Café.

These are based on: the earliest surviving chocolate recipe available from the 1660s; Georgian chocolate similar to what Tosier would have produced; a milky Victorian version; and a modern take, featuring white chocolate flavoured with pineapple. Additionally, chocolate-making demonstrations are held during the first weekend of every month.

So do take time to sit down and reflect upon the colourful characters and their dastardly deeds, and the sheer extravagance of having a servant for the sole purpose of preparing your chocolate. Don’t rush; savour these opulent drinks at a leisurely pace. They are, after all, history in a cup.

Chocolate Kitchen is included in the Hampton Court Palace admission cost of £17.60 for individuals.

Unreal City Audio’s Chocolate House Tour takes place on the third Saturday of every month and costs £15.