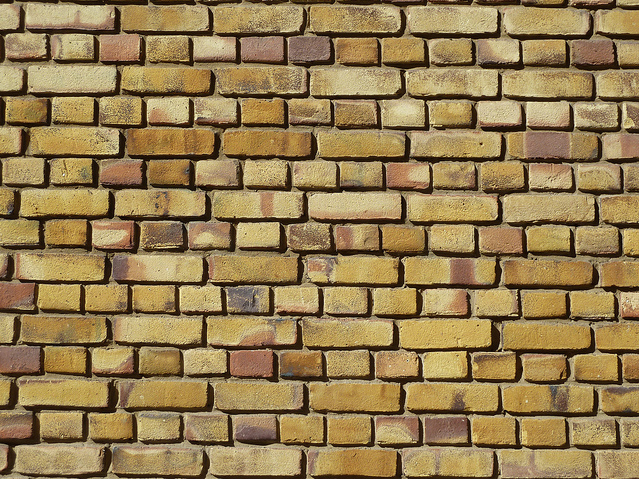

Main image by Lee Jackson in the Londonist Flickr pool.

The London stock brick is an unlikely icon: it is unassuming, unrefined, pock-marked and crinkled like aged skin. Its surface is mottled, with earthy hues daubed grey or black by the smog of industrial London. Because of its handmade quality the contours of each brick are irregular, and no two are the same. This ubiquitous object is the physical residue of a London era, testament to the fire, mud and human sweat that forged the stock-brick landscape of Georgian London.

The brick is the fruit of Georgian topography, fertilised by private wealth. Landowners commissioned brick housing to encompass the entirety of London’s social hierarchy: from the sprawling rows of Hackney terraces, to the squares of Notting Hill, now prettily stuccoed and swathed in wisteria. Today, the yellowish stock brick enjoys a position of veneration in the London cityscape. Even those Hackney terraces are much sought-after, gradually engulfed by the inexorable tide of urban gentrification.

Yet London’s new affection for the stock brick belies its messy conception. Dumbstruck Georgian suburbanites watched in horror as thousands of buildings sprang extemporaneously from the London dirt, rousing a haze of smoke and dust that clogged the city’s widening perimeters for nearly a century.

The process of late-Georgian urbanization tasted of soot and grime. It began with shovels, biting down to expose the innards of the earth, heaving up the dense clay used for brickmaking. London clay is an accumulation of river deposits, the moist detritus of the primordial Thames as it carved its way through the London basin. It maps a material footprint of the river’s wanderings, before London’s barriers limited its movements. London clay is a compact, anaerobic material, ideal for brickmaking. Dense and infertile, it breeds only buildings. The clay's horizontal strata represent the ebb and flow of the river’s course, deposits of varying minerals causing the idiosyncrasies of colour in the fired bricks, “from red, through purple, brown, various shades of yellow […] to off-white”.

Once unearthed, the clay was mixed with water, along with combustible domestic waste, or ‘soil’ — the ash and cinders of the city. This provided inbuilt fuel for the kiln, and imbued the brick with porous pits that allowed for water drainage, generating a brick well-suited to the London environment. This was architectural alchemy, magicking an indigenous building material for London out of the city's own mud and debris. This malleable substance was then pushed into the brick mould, levelled off, and turned out for drying and firing in cavernous on-site kilns.

Between six and eight men would carry out the entire process by hand, smoke in their eyes, the perpetual ooze of mud between their fingers. The firing was not always successful, and sometimes the bricks would fuse together in the kiln, producing “lumps, as big as haystacks [...] burnt into solid masses”. Even so, in an annual summer season a single group of labourers could produce a million bricks, sufficient to build 30 houses.

When the work was complete and the hulking shells erected, the brickfield would be levelled and the whole operation would migrate elsewhere. The period is characterised by a rolling tide of construction, depicted in sardonic glory by George Cruikshank in his 1829 sketch ‘London Going Out of Town or The March of Bricks and Mortar’ (above), in which a band of robotic tool-men march on London’s rural outposts, a surge of brick terraces springing up in their wake. The dome of St Paul’s peeks out from behind a barrage of new houses, while a volcanic kiln spews bricks onto hapless trees and haystacks.

A sign reads ‘This GROUND to be Lett or a Building Lease. Enquire of Mr. Goth, Brick Maker, Bricklayers Arms, Brick Lane, Brixton’. Its linguistic legacy can still be felt across the city: Brick Lane, of course, and Kiln Place in Camden, whilst Notting Hill’s Pottery Lane is still home to an original Georgian brick kiln.

Another aghast observer, Charles Manby Smith, laments the sprawl of brick terraces propagating outside his window: "The smell of the new-mown hay is superseded by the smell of burning bricks; and as for the green fields and the distant hills of Highgate and Hampstead, they might as well be a hundred miles off, for all the good they do us behind a screen of solid brick five or six furlongs in thickness.”

The stock brick is a swelling blight on the landscape, blocking the view. The spontaneous eruption of its suburbs led William Cobbett to christen London with the affectionate epithet ‘The Great Wen’, condemning the city as a sebaceous cyst, an unnatural growth of brick and mortar. Contemporary observations are saturated with bucolic nostalgia, epitaphs to London’s orbital greenery: as for thousands of Londoners before and thousands after them, change and loss are inextricably entwined.

Probably of little consternation to its detractors, in the 1840s the stock brick lost its dominion over London’s urbanization, defeated by geography and chronology. Like with so many aspects of local production, vernacular architecture died with the construction of the railways. London’s capillaries stretched northwards to plumb the resources of other landscapes. The yellow hues of the London stock were abandoned, and pre-fabricated bricks rolled in from the midlands, punctuating the city’s topography with bright red. London continued to swell, but its material link to the landscape was severed – mass-produced brick came first, then concrete and steel. Over the course of the centuries, the stock brick has shifted from villain to hero, eclipsed as the primary material of urbanisation. In a post-war London, this porous brick is saturated with reminiscences, an object made precious by the anxiety of loss.

London shifts. It spurts outwards and upwards in sporadic expansion. Its rhythm is all its own, a palimpsest of migratory nostalgias. London moves, its geology heaving it up and down, inhaling and exhaling through the seasons. It is a tidal city, pulsating with the phases of the river. The inconspicuous stock brick is a single beat in the throbbing tempo of London’s development, but one that still sits rooted in the grit and dirt of its conception, as the undulations of the centuries wash it clean of grime.

By Joyce Dixon