Leigh drives me all over North Ockendon repeating three words, "this is going" as she points to a different structure, or piece of land that will make way for the new road.

I'm in North Ockendon the easternmost part of London. It's also the only part of the capital outside the M25.

North/south divide

Earlier in the day, I've arrived in Ockendon via train. There's no station in North Ockendon — occasional buses are the only form of public transport — but there is a station a mile and a half down the road in neighbouring South Ockendon (in Essex). That station's just called Ockendon, belying the idea that it serves the two areas equally. It's firmly entrenched in the southern region and so it should be. According to the 2011 census nearly 20,000 people live here, compared to 408 people up the road in the London district.

Walking between the two areas takes about half an hour; cars rush alongside as I trudge down the narrow pavement. The road is mainly lined with fields and hedges, until I eventually come to a pair of houses next to each other in the open land. Technically these houses are in Essex, though the boundary to London is just 100 metres down the road and near imperceptible to the naked eye, bar the 'Welcome to North Ockendon' sign.

I'm a little lost to tell the truth. I'm here to meet the aforementioned Leigh. She's a worried homeowner protesting Highways England's plan to build the Lower Thames Crossing. It's a road that plans to cross over into Essex from Kent, wind its way up through the countryside before joining up with the M25 next to Ockendon. It's due to bisect North Ockendon from South, creating a visible boundary between the city and Essex.

I phone Leigh. A head quickly pops out from one of the houses and invites me in. There's a snowboard leaning against one of the walls; Leigh's just back from a trip to Norway. She fetches me something to drink and I meet Roger, another homeowner from further out in Essex, who's also part of the Thames Crossing Action Group, which is against the road.

The road that threatens to change everything

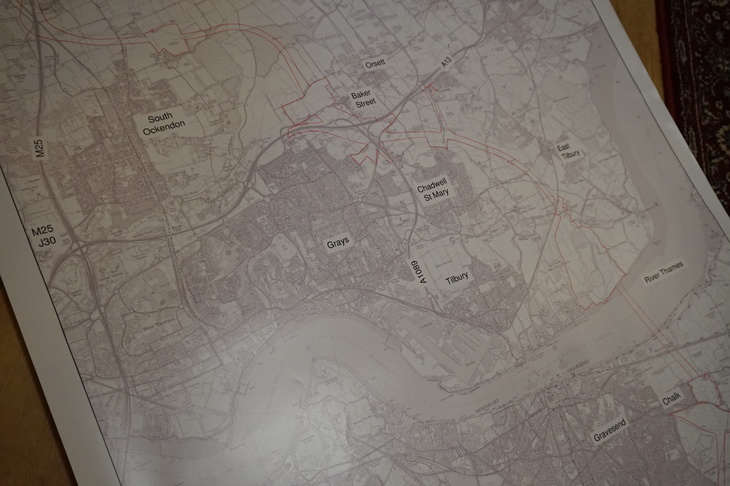

Leigh brings out an A1 map that shows where the route of the proposed road. The locals have numerous issues with it. "We have the M25 here, then there's the A13 and with this new road we're in a triangle of pollution. It will be a toxic triangle."

Leigh continues, "We have a pollution problem." She's not wrong, just a few miles away is Stanford-le-Hope, which regularly vies for the miserable title of the UK's and Europe's most polluted town. This road is only going to bring more fumes to this part of the world, so why is this road such a necessity?

It will be a toxic triangle.

The Dartford Crossing currently can't handle the number of vehicles it takes so needs some relief. Except Roger points out a flaw with this line of thinking. "This road will only take 14% of the capacity of the Dartford Crossing. But by the time it's built, the Dartford Crossing will be running at 117% of capacity." In essence this road doesn't fix much, so surely there's no need for it?

Highways England counters that the road will "provide much needed relief for the Dartford Crossing and improve the resilience of the whole road network."

Says Roger, "That was the original remit for the road, to relieve pressure off Dartford. Then they changed their remit, once their own figures showed that this wouldn't do enough. They ignored other options that would have taken away three times the amount of traffic, but they didn't take away any Green Belt." There it is. That divisive topic: building on Green Belt. To many, it's the only way that London can cope with its continued expansion. To others — usually the ones who live in and around it — building on it is sacrilege.

Building this road on the Green Belt will almost certainly lead to more development in the area. "Highways England reckon, this crossing will pay for itself two and a half times over." The road splits pieces of land, making them near unusable to anyone but developers, which is where the cash comes in. That's why this road is their preferred option.

Tim Jones, project director for the Lower Thames Crossing at Highways England, argues that the crossing offers a "once in a generation opportunity to significantly improve connections between Essex, Thurrock and Kent." It will also create an £8 billion stimulus to the UK economy, he says.

He goes on to admit that he recognises the proposed scheme "could have an impact on local communities," and that they continue to try to understand how best, where possible, to avoid and minimise impacts.

"It's all lip service"

Leigh and Roger are angry at the way the consultations about the road have been handled thus far. "It's all lip service." They point to the fact that even when the road gets such overwhelming negative responses, plans still move forwards. There is to be another consultation later in 2018 — something that Highways England are also keen to point out to us — which they hope will give them a final chance to be heard. But Roger feels ignored, looked down upon, even.

"When you look at the map, this is the only place they can go through. But it's green belt. It's pretty little villages: Ockendon, South Ockendon, East Tilbury, Linford and Orsett. They're all the little nice bits around the area that they're destroying. I don't think it'd happen in Berkshire.

"Thurrock with an f. They think we're all a bit sitting on gates, chewing on a bit of straw around here, and they can do what they like." Leigh interjects: "It is a lovely place to live."

They think we're all a bit sitting on gates, chewing on a bit of straw around here, and they can do what they like.

Another resident we chat to, Peter, disagrees with the notion that the area is under attack because it's in Essex. "I think it is treated differently not because it is London/Essex but because it's on the cusp of the urban sprawl, not heavily populated, so it's easier to walk over people."

Leigh offers to drive me around North Ockendon, so I can visualise what the area stands to lose. We say goodbye to Roger and hop into her car. Houses are sparse here, green is the predominant colour. At one point we pass a pub, and at another a school. But apart from that and a golf course, this must be the emptiest part of London. Still, Leigh looks at what's to be lost and says, "It's heartbreaking".

Though North Ockendon is technically part of London, falling just within the borough of Havering, most locals don't recognise it as such. Says Peter: "I work in Holborn, so London is noise, crowds, pollution, people walking around like robots on mobile phones and there is none of that here."

We end up at St Mary Magdalene Church. It retains architectural elements from the 13th century. The church is safe from the proposed road, even if it will lose some of its parishioners when the new road arrives.

London is noise, crowds, pollution, people walking around like robots on mobile phones and there is none of that here.

Standing outside the historic church, there's a sense of calm. Staring up at the millennia old Grade I listed building, I feel at peace... until I hear the rumble of cars speeding down the nearby M25.

History repeats itself

The most disheartening thing about this fight is that it's all happened before. History is just repeating itself. That's because the M25 didn't used to be there. Residents were forced out when that was built in the 70s and 80s.

Residents were moved for that road too. They saw their home change, so tried to prepare themselves to make sure this couldn't happen again. One owner got a conservation order for his trees, to make sure they'd be protected. It hasn't worked, the new road will tear them up.

Says Leigh, "The reason why I'm fighting this is, you're not safe anywhere if the government decide it's of national importance. But it's the people who can't sell — in the council houses — who are just going to be living with the pollution."

As Leigh drives me back to Upminster station, I realise I've been to Ockendon once before. When I was a child I went to Stubbers, an activity and adventure centre on a school trip. I was only 11 and back then I thought I'd travelled to the middle of nowhere. To many Londoners, the other side of the M25 still is the great beyond. But for a select few, it is both home and London.