In England, the first recorded serving of ice cream was in 1671 or 1672, at a Feast of St George banquet at Windsor Castle.

The lucky recipient of the country's first ice cream headache, we guess, was Charles II and his nearest and dearest.

The event, held to celebrate St George — as well as 10 years since Charles was restored to the throne — featured the following delicacy: one plate of white strawberries and one plate of ice cream.

So rare was this treat, it was only served to the top table: everyone else had to just watch and wonder.

Mrs Mary Eales

The first English cookery book to give a recipe for 'iced cream' was by Mrs Mary Eales, called Receipts of 1718.

A confectioner to Queen Anne, Eales's recipe doesn't include a process for making the ice smooth and it must have been coarse with ice crystals.

Eales's technique involves a lot of ice: she doesn't trouble to explain where the average 16th-century Londoner is going to get that from.

Take Tin Ice-Pots, fill them with any Sort of Cream you like, either plain or sweeten'd, or Fruit in it; shut your Pots very close...

Lay a good deal of Ice on the Top, cover the Pail with Straw, set it in a Cellar where no Sun or Light comes, it will be froze in four Hours.

Despite the clear instructions (you can read them in full, here), ice cream remained a highly prized and very rare treat.

It wasn't until more than a century later that it became readily available on the streets of London.

Bringing ice cream to the people

Swiss entrepreneur Carlo Gatti is credited with making ice cream available to the average Victorian punter.

Gatti came from Canton Ticino, the Italian-speaking side of Switzerland, arriving in London around 1847.

He settled in Holborn's Little Italy, and after running a successful waffle and chestnut stall, opened a cafe and restaurant, specialising in chocolate and ice cream. The latter was a treat that had previously only been available to the very wealthy.

Our entrepreneurial hero had a contract with the Regent's Canal Company for cutting ice for the ice cream from the Regent's Canal.

Gatti then sold ice cream from a stall in Hungerford Market, near the Strand, where Charing Cross station is today, with his nephews working as waiters.

Ice cream as a street snack caught on fast. Particularly popular were 'penny licks', a penny's-worth of ice cream, bought from a cart, and served in a shell or glass.

Hokey Pokey!

Soon, the streets of London echoed with ice cream sellers, shouting their wares: 'Gelati, ecco un poco!' (Ice cream, here’s a little bit!) or 'O che poco!' (Oh, how little! — as in, Oh, how cheap!), which it's believed then led to the bastardised cry of 'Hokey Pokey!'

The term 'hokey-pokey' soon came to mean poor-quality ice cream; sometimes made of questionable ingredients, under unsanitary conditions. It was not at all uncommon for consumers to become ill after eating it.

The way penny licks were served didn't help matters: when you'd finished eating your ice cream, you returned your glass 'penny licker' to the vendor.

He'd either dunk it in some dirty water, or give it a brisk wipe with an ever-present rag, before refilling the glass for the next 'licker'. Boak.

Happily, in 1899, a law was passed to ban the use of penny licks: it was thought that these filthy vessels were contributing to the spread of tuberculosis.

London's ice houses

Meanwhile, Gatti was expanding the backbones behind this growing trend.

In 1857, he built a large 'ice well' capable of storing tons of ice in the Battlebridge Basin off the Regent's Canal. (You can still see his ice house, near King's Cross, which today forms part of London's Canal Museum.)

In around 1860, Gatti started importing ice from Norway. The ice came up the Thames, and transferred to barges at the Regent's Canal Dock (today Limehouse Basin), then along the Regent's Canal to his ice warehouses.

By 1862, Gatti had built a second storage site, and had become the largest importer of ice in London.

He set up a fleet of delivery carts, and supplied ice to rich householders with private ice houses.

Gatti went on to run several other successful businesses in London, including restaurants, cafes and music halls.

A tough way to make a living

There's an incredible description of the lives of London's ice cream sellers by J Thomson and Adolphe Smith, 1877, called Halfpenny Ices.

Part of the Street Life in London series, this particular chapter examines the lives of the Italians living in the Saffron Hill slum in North London (think Fagin's lair, but worse), the majority of whom made a living selling these 'ices'

In little villainous-looking and dirty shops an enormous business is transacted in the sale of milk for the manufacture of halfpenny ices.

This trade commences at about four in the morning. The men in varied and extraordinary déshabille pour into the streets, throng the milk-shops, drag their barrows out, and begin to mix and freeze the ices.

Carlo Gatti has an ice depot close at hand, which opens at four in the morning, and here a motley crowd congregates with baskets, pieces of cloth, flannel, and various other contrivances for carrying away their daily supply of ice.

And there's more

Of course the ices sold give a large profit, but it is from the coloured and water ices that the largest benefits are derived.

The colour, it is true, is an absolute snare and delusion. It generally consists of cochineal, and has no connexion whatever with the raspberries or strawberries which it is supposed to represent.

There really is nothing in these ices but sugar, to which the cochineal adds a certain roughness that produces a titillation on the tongue, fondly believed by the street urchins to be due to raspberries.

This ice is altogether, therefore, a very questionable article, and the less consumed the better the consumer will find himself.

J Thomson and Adolphe Smith thought these ice cream sellers were earning between £1 and £2 a week; it's always tricky to make accurate comparisons, but that could be considered about £100-£200 in today's money.

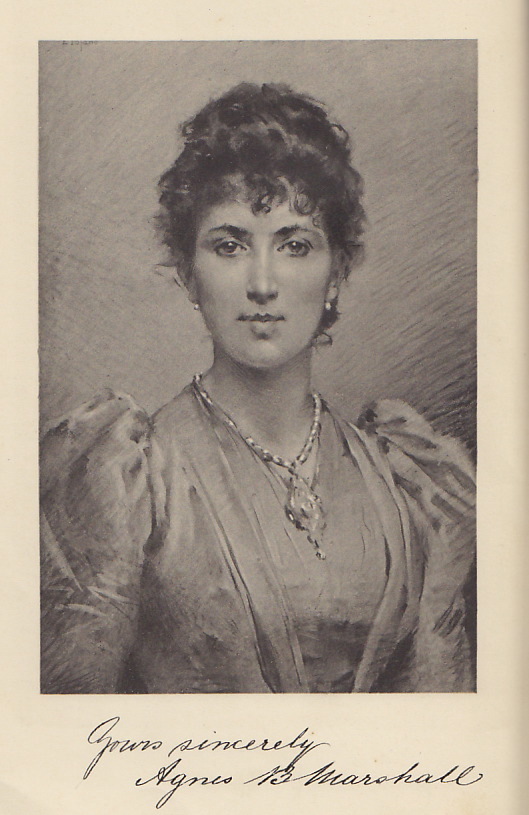

London's Queen of Ices

But Gatti's influence was only part of the ice cream story.

Walthamstow born Agnes Marshall also had a huge influence on ice cream made inside the Victorian homes of the rich and upper middle classes.

An English culinary entrepreneur (who really should be as well remembered today as a certain Mrs Beeton, but her legacy was somehow less well crafted), Marshall was a leading cookery writer in the Victorian period, and was dubbed the 'Queen of Ices' for her works on ice cream.

Her success also increased the demand in London for ice imported from Norway.

Her 1888 cookery book includes a recipe for "cornets with cream", possibly the earliest published description of an edible ice cream cone.

London's first ice cream vans

The first ice cream vans weren't vans at all, but bicycles.

Wall's ice cream was sold from bicycles in London in 1923.

The famous Royal-warrant-holding butchers diversified into making ice cream as early as 1913, to help with the annual summer profits slump, when meat was cheaper.

It wasn't until after the first world war that Wall's ice cream went into production, in a factory in Acton in 1922. It was an immediate success.

In 1924 they expanded the business, setting up new manufacturing facilities and ordering 50 new tricycles. Sales in 1924 were £13,719; in 1927 £444,000.

Walls employee Cecil Rodd came up with the slogan "Stop Me and Buy One" after his experiments with doorstep selling in London.

The distinctive bicycles were stored at the garage on the corner of Aultone Way and Angel Hill in Benhilton, Sutton. (It's still there, if you fancy making a pilgrimage.)