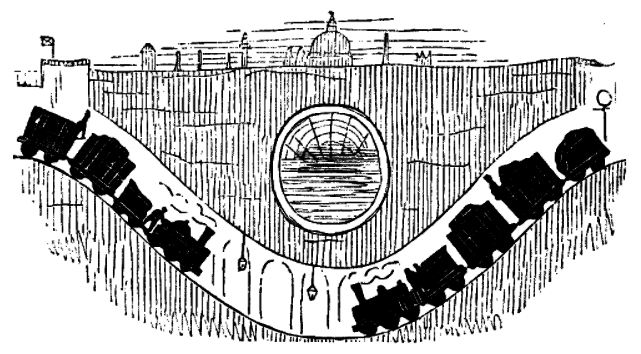

This image of trains pootling along beneath London was sketched in 1846 for Punch magazine. The first underground line did not open until 1863. It's a prophetic view of how the city's transport would develop over the next generation. Even the dangling lamps and arched niches are reminiscent of those at Baker Street station. But where did the notion come from?

The overcrowded city

London in the 1840s was a right old bun fight. New train lines into Euston and London Bridge could bring people into the capital from previously inaccessible distances, but they all stopped on the outskirts of town. An 1846 Royal Commission banned any extensions into the city. Cue, an almighty daily clamour to reach the centre by foot or by carriage.

The roads were clogged. Solutions were needed. Urgently.

One idea, obvious in retrospect, came from the mining industry: build subterranean railways beneath the streets. The crowds would disappear down a rabbit hole without the need to knock down so many buildings. The problem was completely untested in any city in the world but, hey, the Victorians could do anything.

Enter Pearson

The first calls for an underground railway came as early as 1837, when the excavation of the Primrose Hill tunnel seems to have got people thinking. One anonymous writer proposed optimistically that "[a tunnel] from London to Dover would cost less than the tunnel near Primrose Hill". In 1845, a John Williams described a series of underground railways that would also double as conduits for gas and water pipes. There were plenty of other suggestions, though none of them had the political or financial clout to get off the letters pages of the daily newspapers.

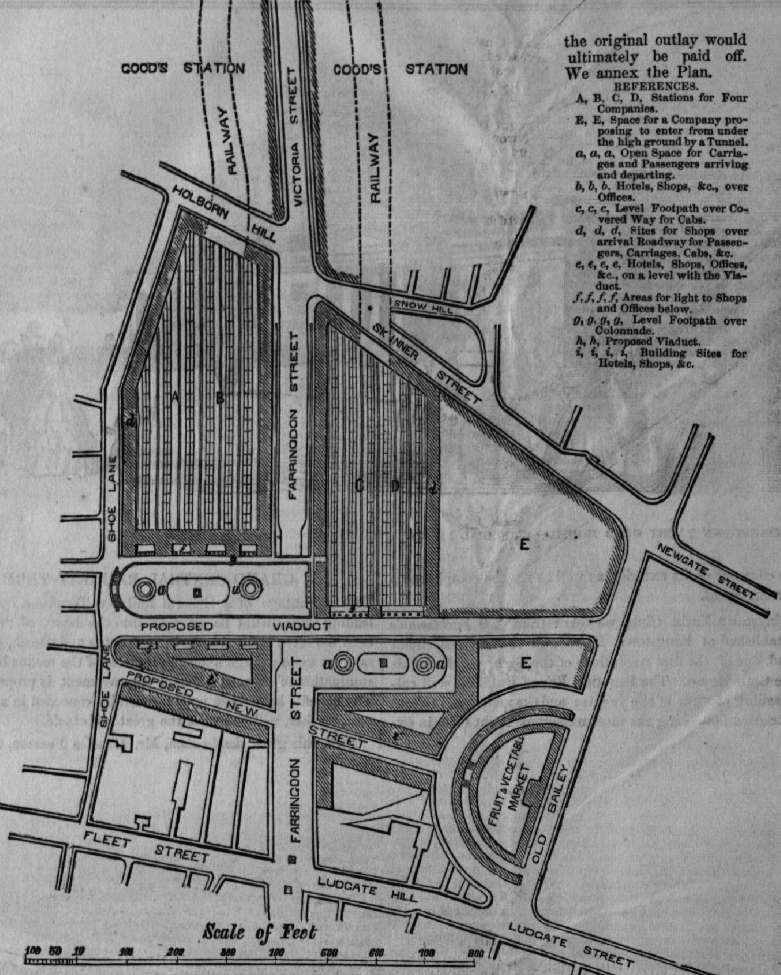

The first serious champion of underground railways was Charles Pearson, Solicitor to the City. In 1846, he presented a scheme to run a subterranean railway from Battle Bridge (beside the modern King's Cross) to a central terminus at Farringdon. Here then is one of the first descriptions of what would evolve into the Metropolitan line.

"Mr Pearson would carry the line of the railway between two rows of houses, which he proposes to build so as to form a spacious and handsome street 80 feet in width and 8505 feet in length. The railway to be on the basement level, and to be arched over so as to support the pavement of the street, which would be on the level of the ground floor of the houses. Mr Pearson proposes to give light and air to the railway by openings in the carriage way and footpath." — The Times 1 July 1846

This vision, which partly prompted the Punch cartoon, isn't far off the Metropolitan line that would eventually arrive 17 years later. The main difference is the location of the terminus which would have been on the site of today's City Thameslink rather than Farringdon. Ian Visits has more.

Pearson lived just long enough to see the first test trains rumble through the Metropolitan line tunnels. Sadly, he died just four months before the service's official opening in January 1863.

In some ways, the Punch cartoon was even more ahead of its time than first suggested. It shows trains travelling far beneath the ground, ducking under a main sewer. This is more reminiscent of the deep level tube lines, which debuted in 1890 with a section of Northern line between King William Street and Stockwell. However, this used electrical traction, rather than the steam engines depicted by Punch.

A tangle of proposals

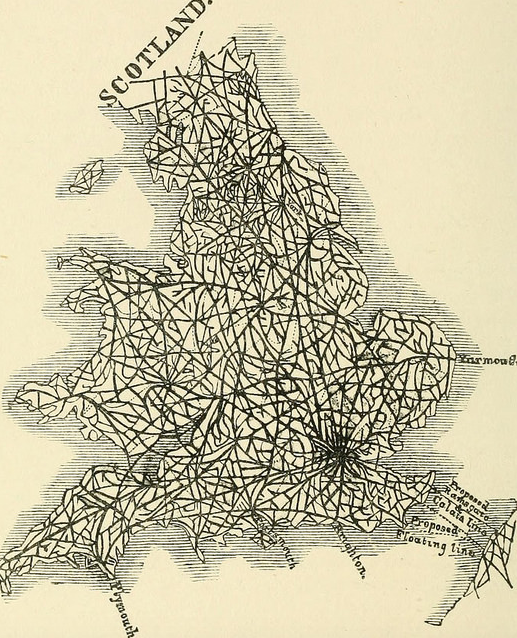

Pearson's ideas came at a time when dozens of proposals for new lines, both subterranean and conventional, were before Parliament. The situation was again parodied by Punch, who threw in channel tunnels and floating railway lines for good measure.

Railway Map of England (A Prophecy). Punch, c.1845. Public domain.

The satirical magazine also suggested linking up the City's church spires with railroads, or running the wheels along opposite roof edges with giant axles spanning the street below. It sounds daft, but the idea is not dissimilar to the Chinese elevated tram:

The frenzy peaked in 1846 when some 272 rail proposals were put before Parliament. Some eventually saw light of day, others were stillborn. One scheme would have seen the Regent's Canal drained and replaced by rail. Another actually did see the Grosvenor Canal pumped dry to make way for Victoria station and its terminating lines. To this day, rail staff at Victoria still talk of 'the beach' area, immediately to the north and next to the bus shelters. The nickname is thought to date back to the station's 19th century watery origins, when this section would have stood on the edge of the canal basin.

The 1846 Punch cartoon may have raised a smirk at the time, but its premise was a reality within two decades. London gained the first true subterranean passenger railway in the world. The tube network is still an icon of the capital today.