“The wooden ladder’s the awful one,” admits Darren Macleod. “It’s 45º and it bounces.” What he doesn’t add is that the ladder is at the very tippy-top of an already perilous climb up an increasingly tight spiral staircase. Oh, and it’s leaning out over London’s highest clock and a hole that plunges pretty much literally to God-knows-where.

An ex-Royal Navy engineer, Macleod’s used to heights: “I used to scale the funnels of the Ark Royal to change the covers.” So when he and Angus ‘Gus’ Collin, climb to the top of St Anne’s church tower to change the flag, it’s more like keeping a hand-in than dicing with death.

St Anne’s is a contender for 18th century architect Nicholas Hawksmoor’s most mysterious creation so of course that flag isn’t just any old drape. It’s a White Ensign, usually flown on Royal Navy ships. What’s it doing there?

Cue a wibbly-wobbly timeslip…

The Dull-sounding New Churches Act was passed in 1711. “The idea was to echo the 50 churches Christopher Wren built in the City after the Great Fire by erecting 50 more in the rapidly-growing suburbs,” says local expert Michael Hebbert.

“Hawksmoor wanted grandeur and he used every trick he could to make it look huge. Vast temples, looking back to the churches of Rome and Byzantium with a grand processional route.”

St Anne’s was the first scientifically-oriented church. Hawksmoor used Edmund Halley’s new method of correcting magnetic compass readings to ensure the altar faces east. “It’s actually one degree out,” admits Hebbert.

The crypt, so big it was used in the second world war as an air-raid shelter, is actually above ground, making the church even taller. There’s a reason for this, and it brings us back to that flag.

St Anne’s has been a Trinity House ‘sea mark’ on shipping charts for centuries. Even relatively recently two new blocks of flats were forced to drop a couple of floors to keep the seven-foot golden ball visible from the river.

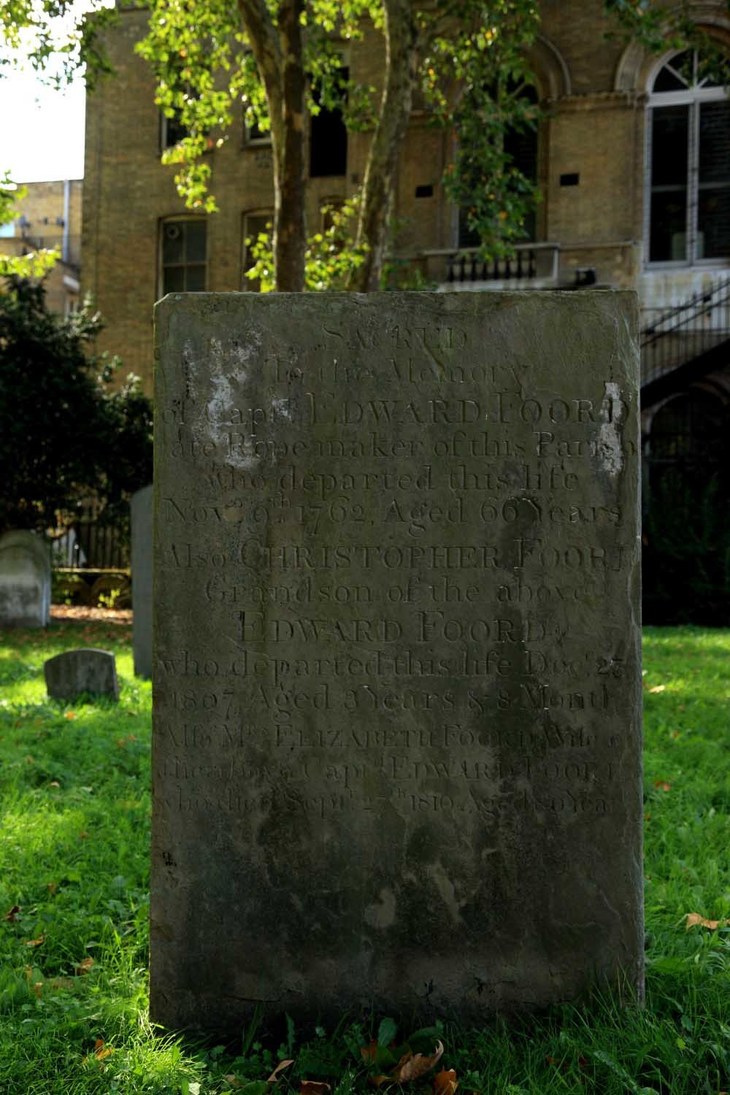

Sailors needed churches for births, marriages and burials and the church designated for merchant ships was St Dunstan’s, a mile away.

Generally, only ships’ captains could read and write but every seaman understood a flag. St Dunstan’s flew the Merchant Navy’s Red Ensign (AKA ‘Red Duster’), to direct sailors to the right place. St Anne’s received a rare honour, the White Ensign of the Royal Navy. Even today regulations dictate that ‘Commanding Officers should take appropriate steps’ if they catch anyone flying the White Ensign at unauthorised locations.

Flags must be taken down each sunset and re-hoisted at sunrise. One look up that ladder though, and it’s clear no one was ever going up St Anne’s tower twice a day. Queen Anne’s special dispensation still appears in Queen’s Regulations: BRD 9148 Sch.1B [pdf].

The White Ensign’s refreshed two to three times a year. “I return the old flag to HMS President [the Royal Navy’s reserve building, near St Katherine’s Dock] and exchange it for a fresh one,” says Darren Macleod.

“Richard (Bray, the rector) likes to have a clean flag for Remembrance Sunday,” adds Gus Collin.

After some experimentation, Macleod has settled on two different sizes: 12 feet by six feet and 18 by nine. “The smaller flag doesn’t look so good but it’s more durable for winter months.”

Getting up there, even without an 18ft flag is quite an experience, not least because of the church’s sheer size.

“The nave is colossal,” says Michael Hebbert, “but it’s nothing in comparison to the bits you don’t see.”

On each side of Hawksmoor’s imposing entrance sit two smaller towers. “They act like shoulder pads,” says Hebbert.

Two giant, cavernous staircases climb to the first floor. One has its original wooden bannisters, complete with painful studs to deter choirboys sliding down.

The other, victim of a disastrous fire that engulfed much of the church on Good Friday, 1850, is Victorian.

Odd, low doors, halfway up, hint at rooms behind; it’s soon clear St Anne’s is honeycombed with unused — and unusable — secret spaces.

Stopping briefly at balcony level, Michael Hebbert opens the grand organ which, thanks to a recent grant, has been fully restored.

“It came from the 1851 Great Exhibition,” he says, demonstrating the newly-repaired hand-pump.

“The Grand Bombard stop still gives quite a thrill.”

St Anne’s is not a wealthy church.

For the most Christian of reasons, the parish still puts people before pomp, preferring to spend what money it has on community outreach rather than dusty fabric.

Parapets have blocked with fallen leaves, leading to ingress and catastrophic collapse of plaster work.

Stained glass windows are distorted and thick with candle soot.

We’re lucky to have the church at all. By the end of the 1960s the East End’s population had dwindled and the church was dilapidated. Thanks to a spirited campaign St Anne’s was listed and now the community thrives again.

One of those small staircase doors leads to dark, spiral, stone steps. The bell ringers’ practice room, inside the domed wooden ribs of the front entrance is relatively easy-access.

Other vast, empty chambers are less so.

Grand, double-height, they’d make great function rooms – if you could get inside.

As it is their entrance-doors are at convenient bends in the spiral, a metre or so up the wall.

After the ‘shoulders,’ in the tower-proper, the steps get even narrower.

Stonemasons have cut shallow curves into the undersides to save heads, but even small shoulders are crammed tight.

It’s almost a relief to clamber down into the clock chamber.

Built by Moores of Clerkenwell the highest timepiece in London’s a delight to see, possibly not an opinion shared by whoever had to wind it by hand right up to the 1980s.

And finally that 45º ladder, teetering up to a tiny hatch. “When I started here, the ladders were inch-thick with pigeon guano,” says Macleod. “It’s still not a nice climb, but it’s worth it when you get to the top.”

“A 360º view of London, over the Barley Mow Estate,” adds Collin.

Peering down through the Victorian plane trees, it’s possible to make out St Anne’s most famous ‘secret.’ A pyramid in the churchyard, beloved by conspiracy theorists and ley-line mongers alike, has endured sinister rumours for years - it even appears in the dodgy 1930s Fu Manchu mysteries as the entrance to the evil doctor’s opium den.

The truth is, alas, boring. Hawksmoor’s plans clearly show he intended two pyramids, merely as decoration. One got lost or broken; the other never made it beyond the churchyard.

Far odder in Londonist’s book is the strange upside-down-right-way-up gravestone nearer the street, which can be read either way up depending on which side you stand. What’s its story? Who knows.

St Anne’s is a genuinely mixed East End church. Everyone is welcome to join the regular services and meetings. Contact Rev. Richard Bray for more details.

Images © Sandra Lawrence, Angus Collin, Ian Dunnigan and Matt Brown.