It's amazing what's lurking down London's back streets. Christopher Winn, author of the popular I Never Knew That About London, picks out six of his favourite Victorian gems. Their stories are taken from his book Walk Through History: Victorian London.

1. 25 Cadogan Gardens, Chelsea

This was built in 1894 as a studio home for a friend of JM Whistler, the Australian-born artist Mortimer Menpes. The architect was Arthur Heygate Mackmurdo. The slender square columns with flat square tops framing the front door are a design unique to Mackmurdo. Note also that the north-facing windows are oriel windows and much more lavish than the west-facing windows, reflecting the importance of the north light to artists. The house is now owned by Peter Jones, the large department store that backs on to it.

2. 91-101 Worship Street, Shoreditch

This unique terrace was built in 1863 and designed by Philip Webb, architect of the Red House in Bexley. Webb usually designed individual domestic buildings but was asked to build this terrace of affordable artisan's workshops, shops and houses as a charitable commission. The architectural style is simple Gothic, but the pointed brick window arches and steep roofs are early signs of the Arts and Crafts style that Webb would later develop with Morris.

Basement windows allow light into the workshops below while the large shop windows allowed the artisans to display their wares. The big dormer windows provided light for artists at the top of the house. There is even a Gothic drinking fountain (far right) to complete the Victorian good works theme.

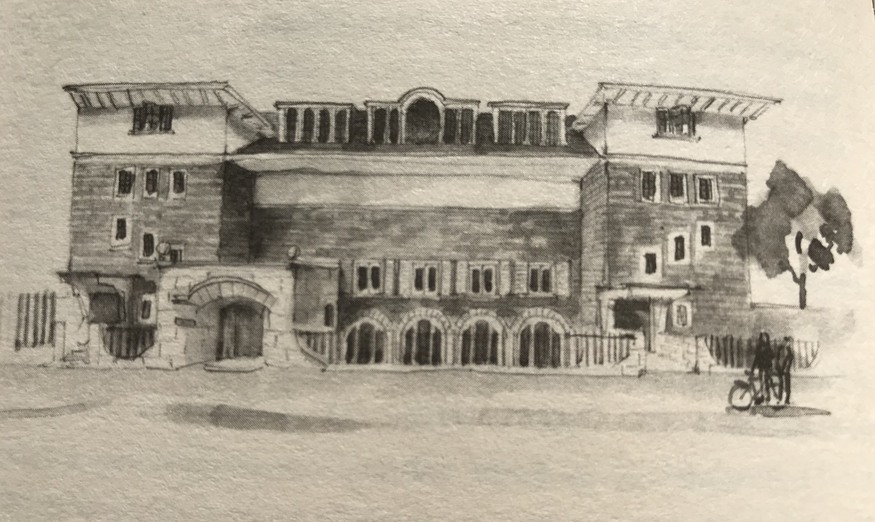

3. Mary Ward Settlement, Bloomsbury

Perhaps London's finest Arts and Crafts building, certainly one of the first public buildings to be designed in the Free Style of that movement. Built in 1897, it is the work of two young local architects, Cecil Brewer and Arthur Dunbar Smith, who won a competition judged by Norman Shaw. There is indeed a hint of Norman Shaw about it and also a whisper of Charles Townsend, he of the Whitechapel Art Gallery.

At first glance the front of the building is symmetrical, with the obvious exception of the huge stone porch, but on closer inspection the symmetry dissolves — have a look at the positioning of the two identical side doors and the stepped windows above them. Such details make this building never less than interesting.

What became known as the Mary Ward Settlement was established in 1890 by the eponymous novelist. It was modelled on Toynbee Hall in east London. The settlement moved to Queen Square in 1982, and Mary Ward House, as it is called today, is now privately owned.

4. Parnell House, Streatham Street, Bloomsbury

Parnell House was built in 1849 by the Society for Improving the Condition of the Labouring Classes as part of the slum clearance of St Giles rookery. It was one of the very first model dwellings designed to offer healthier and more spacious accommodation to families who had been living crammed together in one room. Parnell House was, in fact, the first multi-level domestic building in the world, another Victorian first.

Each flat had a minimum of three bedrooms, and its own scullery, water supply, WC and fireplace. The architect was Henry Roberts, one of the first, most innovative and most influential of those sterling Victorian characters who determined to improve the living conditions of the poor. Roberts is also known for rebuilding London Bridge railway station in 1844.

5. St Michael's Vicarage, Burleigh Street, Covent Garden

Standing out in red brick with stone dressings and decorated with yellow-brick diamonds, this delightful little house is squeezed into an L shape by its corner plot. It was built by William Butterfield, architect of All Saints, Margaret Street, in 1860, to serve as a vicarage for St Michael's Church, which stood where the Strand Palace Hotel is now. The church was demolished in 1906 and the house then became a clergy house for St Paul's, Covent Garden.

6. The Old Pump House, Kensington Court

Here is evidence of one of the many ingenious innovations that make Kensington Court so interesting, in this case hydraulics. Hydraulics was the latest thing in the 1880s, a clean, quiet and reliable alternative to steam, and Jonathan T Carr, the original developer, wanted all the houses to have hydraulically operated service lifts instead of back stairs. To this end he prevailed upon the newly formed London Hydraulic Power Company to build a pumping station just for Kensington Court.

Water drawn from the Thames was pumped from the Old Pump House here to the other houses through pipes running along subways dug under the road. This was the very first time an independent hydraulic system had been used to power domestic houses anywhere in Britain, possibly the world. Gradually, Kensington Court was weaned off hydraulics and onto electricity. The Pump House was converted into rather a nice residence.

Abridged extracts taken from Walk Through History: Victorian London by Christopher Winn. Illustrations, taken from the book, by Mai Osawa.