Being the head of the Garden Bridge Trust can’t be an easy job at the minute. There’s vocal opposition — we’ll come onto the detail in a moment — to the extent of parodying the bridge in the form of a scrotum, and an unfolding procurement scandal. But Bee Emmott is relentlessly upbeat about her task.

“I think projects of this nature will always stimulate debate,” she says. “It’s an ambitious, unique project, a bit like the Millennium Wheel. People were up in arms and now you wouldn’t dare take it down.”

The Garden Bridge Trust (GBT) is a charity that was set up to raise funds to build and maintain the bridge, and oversee its construction. It took over the project from Transport for London (TfL) and will be responsible for looking after it once it’s up and spanning the Thames.

“We’ve raised £145m to date. £60m of that is from the public sector and then all the rest is private sector funding. The total cost for the project is £175m but that’s broken down into things like £22m VAT, contingency and operations.” About that £60m; when the bridge was first announced, Londoners were promised that not a penny of public money would be needed. What happened?

“We’ve got a unique [funding] model, in terms of the public funding unlocking such a significant amount of private investment," Bee says. "It’s very difficult to raise private funds in the UK, particularly when we have a very different kind of philanthropic culture than, say, America. You just wouldn’t get that without having some kind of public funding there to help the project get through the beginning stages so it becomes viable.”

Bee goes on to elaborate the transport case for the bridge, which is the justification for TfL and the Treasury each contributing £30m. “If you look at the frequency of bridges in central London, this area is actually the biggest stretch in central London where there isn’t a bridge. The Garden Bridge can’t be seen in total isolation, you’ve got to look at it in terms of TfL’s wider strategy and transport wider throughout London.

“There’s need for bridges east and west for sure, and this is not denying that’s the case. This is much more about an additional link right in the centre of town that will encourage people to walk. At Waterloo station now, it’s highly congested and people take tube journeys from Waterloo to very short distances away because the walking experience between Waterloo and, say, Covent Garden at the moment is just not a pleasant one.”

Modelling done by the GBT suggests 27,000 people will use the bridge every weekday, 9,000 of whom will be commuters. Given its hybrid appeal of actual bridge and tourist attraction, the modelling predicts peaks of up to 4,500 people mid-afternoon, primarily comprised of tourists. On Saturdays footfall is expected to reach up to 30,000, whereas Sundays are expected to be quieter, with around 18,000 visitors.

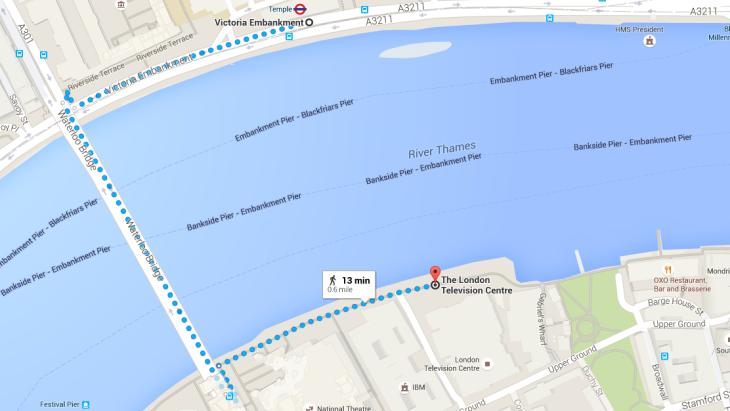

These figures are comparable with Millennium and Tower bridges, and significantly higher than Waterloo and Blackfriars bridges. And yet. Bee says it’s been modelled that the Garden Bridge will take 12 minutes to cross “at a reasonable pace”. This seems like a long time to us; Google Maps reckons you can cross Waterloo bridge in just five. Weirdly, it also says that if you start at one of the points where the Garden Bridge will land, walk to Waterloo bridge, cross the Thames and walk to the other landing point, it will take 13 minutes. Why on earth would anyone looking for a quick, simple route from A to B take the Garden Bridge?

“Waterloo Bridge is not an enjoyable pedestrian experience,” says Bee. “If you go through rush hour, it’s a bit like hell! There are quite a lot of schools, particularly in the Covent Garden area, where a lot of the community on the south side go. Waterloo Bridge is very much dominated by cars and buses and that’s its main purpose. It’s not made for pedestrians particularly. I think what the Garden Bridge does is offer an entirely different route that’s putting the pedestrian first.”

During our conversation it becomes clear that the vision for the bridge is for a lovely experience away from polluting vehicle fumes. This may be why it takes 12 minutes to cross; it won’t be somewhere for commuters to charge, head down, on their way to work. It’s for people who need to be exactly where the bridge lands, have a bit of time or prioritise their surroundings over speed. Cyclists, however, are consigned to Waterloo or the forthcoming cycle superhighway over Blackfriars Bridge — all bikes have to be pushed across.

With experience more important than efficiency, what about concerns the bridge might become overcrowded at peak times and people having to queue? Bee is adamant that the modelling suggests this won’t happen. “The maximum number the bridge can take at any one point is about 2,500 people, but that’s a worst case scenario if everybody was still,” she says.

The Garden Bridge offers an entirely different route that’s putting the pedestrian first.

“If you look at pedestrian modelling of other areas of London, people self-regulate to a certain extent, so we anticipate that the Garden Bridge will be the same in terms of the people flow. We don’t anticipate queues [but] we do have mechanisms if there are queues.” Temple station’s roof could be used as a waiting area, and there will be a similar building on the South Bank, where people could queue out of the way of people passing below.

We then ask about concerns that visitors will be tracked by their mobile phones. “You can’t track people,” Bee explains. “It’s the same as the royal parks, you can’t track people like ‘Bee Emmott’ but if I’ve got a mobile phone they can track ‘a unit’.”

The mobile phone story tapped into an increasing concern Londoners have about nominally public spaces that are actually privately controlled. The bridge will be mainly privately funded and privately run — and closed overnight. Will there be security guards patrolling?

“The bridge is privately owned by the charity, like the royal parks are privately owned by a charity, but it’s publicly-operated. This is not meant to be a place which is highly managed. It will feel like you’re just walking in a garden. We’ll have people there, like gardeners and visitor hosts to help with directions and so on, but the feeling is very much about you being in a garden and not being managed in any way at all. The visitor hosts will be helping tourists with directions, that sort of thing.”

Bee also expands on how prominently donors will be acknowledged, following news that Sky has got naming rights over one of the garden areas. “We don’t have the ability to name the bridge, the 'Sky Garden Bridge' or whatever. That’s absolutely not the intention anyway. What we’ve got is very discreet naming opportunities where people get acknowledged on the bridge in different places. It has to fit in with the look and feel of the bridge, it’s not about loads of names everywhere and feeling like Disneyland.”

In the end, Bee feels the bridge will win out. “I guess this is about something that’s just so unique. People say London’s the thought leading capital of the world. If you look back at the Olympics, we all moaned about it and then it was amazing and we congratulated ourselves about how amazing we are and look what we managed to achieve. There’s something about making something happen that is amazing, completely innovative and completely exciting and special and feeling really proud that you can do that. That is also something that the Garden Bridge is about, being at the top of our game and doing something special and that no-one else has done before."

This upbeat finale, however, came before a new wave of negative publicity. In the last week, Richard De Cani, the man at TfL who creating the 'scoring' process for selecting the winning design — by Heatherwick Studio and Arup — has joined Deputy Mayor for Transport Isabel Dedring in going to work for Arup. Or, in De Cani's case, re-joining, as he's worked there before. The controversy over how Heatherwick won the contract has reached the London Assembly, where a motion put forward by Caroline Pidgeon urging TfL to recover public money from the Trust passed 12-7 on Wednesday. Kate Hoey, the MP for Vauxhall, is asking the National Audit Office to investigate. Even the president of RIBA thinks the bridge should be put on hold.

We'd asked Bee Emmott about the unfolding claims when we met, and the Trust is in the awkward position of running the project but having had no say in this procurement. "We feel that it’s very historical, it happened before our time. There’s not much more we can say," she explained.

Time is not on the side of the Garden Bridge. It needs to be finished before construction on the Thames Tideway Tunnel starts in 2018 — the two projects plan to make heavy use of the river, and the Port of London Authority is not keen on both of them competing for space — which means work on the bridge needs to start this summer. Lambeth Council has imposed some planning conditions, more than half of which have been met, but any delay created by an investigation into how the plan got (metaphorically) off the ground could scupper the whole thing.