As we approach the General Election on 7 May, the think tank Centre for London looks at the big issues shaping electoral politics in the capital. By Lewis Baston.

London is often referred to as a ‘Labour city’ — to the extent that it risks becoming a political cliché. The idea has its political uses, particularly among the Conservatives — to excuse poor electoral performance, or alternatively to make the personal achievement of Boris Johnson in getting elected its mayor twice look even more impressive.

But on closer inspection it is not true — or true only very recently. Labour and the Conservatives have both won five elections for control of London government on its current boundaries, if we count Ken Livingstone’s independent run in 2000 as being Labour. Before 2010, the winning party nationally has always won London as well, with the arguable exception of a couple of elections where the result was close and the winning party in seats and votes was different (1951 and February 1974).

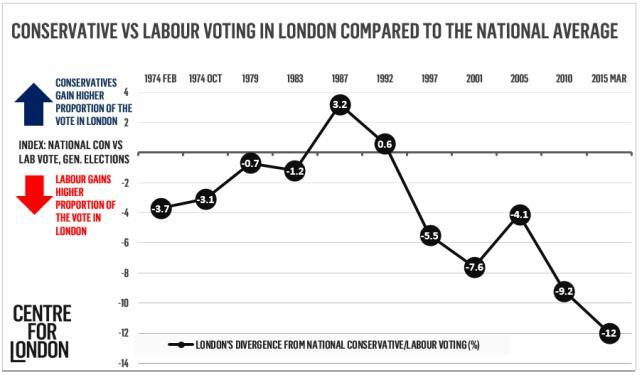

London is therefore traditionally a marginal city. It has a slight tendency to overdo it when there is a large national movement of opinion, with above-average swings to the Conservatives in 1979 and Labour in 1997. The table below shows the percentage of votes for each party in London since the constituency boundaries recognised the modern (Greater) London in 1974. The ‘London gap’ columns are simply the difference in the Conservative lead over Labour in London from what it was in each election first in Great Britain (including London) — the national verdict — and then from the Tory lead in England outside London.

| Votes | Con % London | Lab % London | Lib Dem % London | Con lead over Lab London % | ‘London gap’ from GB vote lead % | ‘London gap’ from rest of England % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1974 Feb | 37.6 | 40.5 | 20.8 | -2.9 | -3.7 | -6.4 |

| 1974 Oct | 37.4 | 43.9 | 17.0 | -6.6 | -3.1 | -6.3 |

| 1979 | 46.0 | 39.6 | 11.9 | +6.4 | -0.7 | -4.8 |

| 1983 | 43.9 | 29.8 | 24.7 | +14.0 | -1.2 | -5.8 |

| 1987 | 46.5 | 31.5 | 21.3 | +15.0 | +3.2 | -2.0 |

| 1992 | 45.3 | 37.1 | 15.9 | +8.2 | +0.6 | -3.7 |

| 1997 | 31.2 | 49.5 | 14.6 | -18.3 | -5.5 | -9.7 |

| 2001 | 30.5 | 47.4 | 17.5 | -16.9 | -7.6 | -12.2 |

| 2005 | 31.9 | 38.9 | 21.9 | -7.0 | -4.1 | -8.4 |

| 2010 | 34.5 | 36.6 | 22.1 | -2.1 | -9.2 | -15.7 |

London has generally been fairly Conservative, given its urban characteristics. In 1987 and 1992 the Conservatives were actually further ahead in London than they were nationally, and they also won the capital’s vote handily in 1979 and 1983. But the general election of 1997 seems to mark a lasting change in London’s preferences, which, unlike previous fits of enthusiasm for one party or another, did not go into reverse once the tide started to ebb nationally. The only recent dip in the capital’s trend towards Labour was in 2005, and then the deviation was less about a swing to the Tories than Labour losing ground to the Liberal Democrats, Respect and the Greens after the Iraq war. The low swing to the Conservatives in 2010 did more than just correct for the result in 2005; it may be the point at which we can say that London really became Labour, rather than just swingy as its enthusiasm for Thatcherism and New Labour might have suggested.

But what about 2015? Most of the evidence we have suggests that London will retain its recently-acquired Labour status, but that the gap between London and the rest of the country may not have become any wider since 2010. Recent London polls by YouGov for the Evening Standard have shown Labour with an 8-12 point lead, a 3-5% swing since 2010 and equivalent to Labour and the Conservatives being neck and neck nationally, which is more or less what the other polls have been saying. The London Assembly election in 2012 had Labour 9 points ahead, and in 2014 the borough elections showed an 11 point lead and the Euro elections a 14 point lead. What has been noteworthy in London voting since 2010 is that it has proved stony ground for UKIP, who won the 2014 Euro election nationally but came third in London, and currently stand at 10% in the London polls compared to the 14% they score in comparable national polls.

London’s recent trend towards Labour owes much to its accelerating ethnic diversity; it became a ‘majority-minority’ city by the time of the 2011 census, and black and minority ethnic voters are consistently loyal to Labour. London’s youthful, liberal population and large numbers of public sector workers also tend to add support to the parties of the liberal left. But it should not be forgotten that London also has huge concentrations of wealth and a massive financial sector but very little industry, and that many people who would otherwise vote for the left are either not permitted to in general elections (most EU migrants) or have trouble getting onto the electoral register (young people and ‘Generation Rent’). London should be fairly good ground for Labour in 2015, but we should not expect the swing to diverge hugely from the national verdict. The next article will look in more detail at where we might expect seats to change hands, and why.

Lewis Baston is a Research Associate at Centre for London and writes on elections, politics and history. He is a frequent commentator for various broadcast, published and online media.

@centreforlondon

@lewis_baston