The Hard Problem Stimulates The Brain More Than The Heart

Last Updated 31 January 2015

Londonist Rating: ★★★☆☆

The Hard Problem is the much-anticipated first new play in nine years from arguably Britain’s greatest living playwright Tom Stoppard, and the last production of Nicholas Hytner, after 12 highly successful years as the National Theatre’s artistic director. With this in mind, it's sadly also a bit of a let-down. ‘The hard problem’ at the centre of the play is the elusive nature of human consciousness: are our thoughts and emotions all merely determined by a complex interaction of electrical and chemical signals between nerve cells, or do we have minds/souls separate from our bodies that give us our sense of personal identity and free will?

Stoppard explores these sorts of questions in the setting of the fictional Krohl Institute for Brain Research, where young psychology graduate Hilary is determined to prove that not all human behaviour can be attributed to a materialist or evolutionary explanation in which ‘the selfish gene’ predominates, and that genuine altruism is possible. Olivia Vinall plays her with an attractive vulnerability, conveying authentic goodness of intention. It turns out that Hilary has very personal reasons for her research — having had to give her baby girl up for adoption as a 15-year-old — which goes against the ethos of the institute.

Meanwhile, sympathetic boss Leo is under pressure to survive from the billionaire hedge fund founder Jerry Krohl, who is more interested in predicting how people will act in the financial markets.

From game theory’s ‘the prisoner’s dilemma’ and ethical philosophy to artificial intelligence and neuroscience, Stoppard characteristically plays with a bewildering number of ideas. He does so with admirable lucidity and illuminating wit. But while our intellects are stimulated, our feelings are not much engaged. Apart from perhaps Hilary — whose back story returns in a predictable but unconvincing fashion — none of the other characters are fully rounded, so the play tends to come across more as an entertaining debate than a fully-fledged drama.

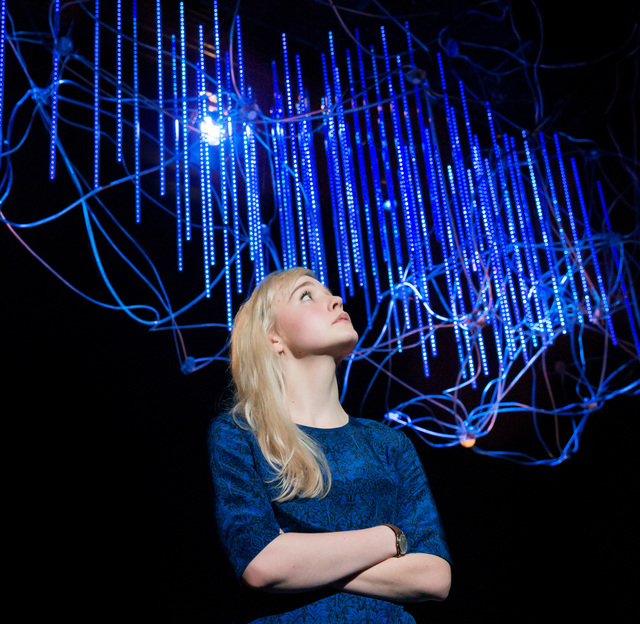

Hytner directs with his customary elegance and precision, while Bob Crowley’s suspended, colour-changing mass of rods and wires evokes the flashing pulses of neurons in the brain and Bach’s contrapuntal preludes played on piano suggest restrained but deep emotion.

There's much to admire from the supporting cast: Jonathan Coy’s concerned Leo proves to have ulterior motives, and Anthony Calf’s Jerry is a disarming mixture of ruthlessness and generosity. Damien Molony plays Hilary’s on/off boyfriend ex-tutor with clinical humorousness, Parth Thakerar is an ambitious mathematician who starts to believe in irrationality and Vera Chok is a brilliant but flawed researcher.

The Hard Problem is a play showing the limits of scientific materialism, but unfortunately, there's a limit to its own dramatic impact.

By Neil Dowden

The Hard Problem is on at the Dorfman, National Theatre, SE1 until 27 May. Tickets are £15-£50. Londonist saw this production on a complimentary ticket.